Citation: Babcock and Booth (2020) Managing Large Gulls. Tern Conservation Best Practice. Produced for “Improving the conservation prospects of the priority species roseate tern throughout its range in the UK and Ireland” LIFE14 NAT/UK/000394’

Last updated: October 2020

This is a live document we update regularly. If you have comments and suggestions, please email Chantal.Macleod-Nolan@rspb.org.uk

Last updated: October 2020

This is a live document we update regularly. If you have comments and suggestions, please email Chantal.Macleod-Nolan@rspb.org.uk

| Babcock and Booth (2020) Managing Large Gulls. Tern Conservation Best Practice. | |

| File Size: | 1330 kb |

| File Type: | |

Key Messages

- Large gulls can have a significant adverse effect on tern colonies in two ways: firstly by predation of eggs, chicks or fledglings, and secondly by taking over breeding habitat and displacing breeding terns.

- All the large gull species in the UK are declining and either red or amber listed and a metapopulation approach is needed to avoid detrimental impacts of tern conservation on gull populations

- Disturbance methods can be employed to minimise the need for lethal control of large gulls

- Removal of eggs is considered a form of lethal control and requires a licence from the relevant statutory agency, killing individual gulls which are specialising in predating terns may also sometimes be necessary to ensure tern populations persist.

Information

Large gull species (in the UK and Ireland these are herring gull Larus argentatus, lesser black-backed gull Larus fuscus and great black-backed gull Larus marinus) can have an adverse effect on tern breeding colonies, either by predating or displacing terns. In the past, large gulls have sometimes been culled on nature reserves for conservation reasons, however most conservation land managers will want to minimise the use of lethal control methods as herring gulls is on the Red List and lesser black-backed and great black-backed gulls are on the Amber List in Birds of Conservation Concern 4 (Eaton et al. 2015).

One way of minimising the need to employ lethal control methods, is to keep areas free for breeding terns by preventing large gulls from attempting to breed using disturbance techniques. These are most effective in the pre-breeding period before birds set up territories, and before the terns arrive. However, studies have shown that large gulls will often habituate to disturbance over time and so disturbance is most effective when a suite of techniques is used and also when it is backed up with occasional lethal control (e.g. Cook et al. 2008).

It may still be necessary to remove large gull eggs and nests, especially where the aim is to prevent displacement of tern colonies. This is legally considered to be a form of lethal control and must be done under licence from the relevant statutory agency.

Targeted lethal control of individual gulls which specialise in predating tern nests or young is also likely to continue to be a necessary part of colony management, and again must be done under licence. Accurately identifying individual gulls is labour-intensive but necessary to ensure that this is kept to a minimum.

Colony managers will need to assess what is practical at each colony on a case-by-case basis and to continue to adapt the methods used as knowledge develops and as gulls change their behaviour or habituate to existing methods of management.

Disturbance Methods

A number of techniques have been trialled to deter large gulls from breeding on Coquet Island, Northumberland, which is managed by the RSPB. These were reviewed in Morrision & Allcorn (2006) and the most effective were those incorporating loud bangs (which could not be used in the breeding season because of the disturbance to other species, but were useful pre-breeding when only the large gulls were present), gull distress calls which were moderately effective and could be used at any time of year, and physical human presence.

Laser hazing has recently been trialled as a method of deterring large gulls and other avian predators at a number of tern colonies in the UK and Ireland, including Coquet Island, the Skerries, Rockabill and Hodbarrow and little tern colonies at Gronant, the Long Nanny and Chesil. Lasers to disperse birds are sold under the trade names Agrilaser (for crop protection) and Aerolaser (a more powerful and expensive model intended for use at airports). The laser is aimed at the ground and the laser ‘dot’ moved toward the bird; a process referred to as ‘hazing’. The manufacturer claims that birds perceive the dot as a threat and do not become habituated. RSPB trials of aerolasers are ongoing and it is too soon to assess effectiveness and habituation.

Anecdotal reports on the use of the laser to deter settlement suggest mixed success, as would be predicted by the manufacturers guidelines which suggest that the effective range is greatly reduced in strong light. The suppliers websites offer further information. On Rockabill an Agrilaser pointed at the unoccupied island of the Bill and moved around the areas where gulls were present was extremely effective in low light levels, causing gulls to take off almost immediately, but during daylight hours was ineffective apart from on extremely overcast or misty days (Rockabill Tern Report 2019). At Hodbarrow a laser was generally considered to be effective throughout the day, when used at relatively short range from a hide overlooking the tern breeding area (Dave Blackledge, RSPB Cumbria Coast, pers. com.). On Coquet Island the laser has been successful as a settlement deterrent (see case study), although the effectiveness has varied in different light conditions.

Some sites also attempted laser hazing to deter predation attempts, and preliminary analysis these results suggests that hazing reduced the probability of a predation attempt but that hazed predation attempts were more likely to be successful, perhaps indicating that a predator that is more certain of taking prey is less likely to be distracted.

Managing territorial large gulls

Often despite best efforts at discouraging large gulls from settling, a few will still attempt to nest in areas which are specifically manged for terns. Once established on a territory displacement methods are unlikely to work. At this point, if it is possible to do so without serious disturbance to other species, and subject to having the appropriate licence agreements, the only available measure is to remove nests and eggs. If the aim is to avoid displacement of terns (and if no gull census figure is required) then it is best to do this as soon as possible and continue monitoring, as territorial pairs will sometimes re-lay within the territory but in a new nest. If the aim is to minimise predation pressure, the key is to remove eggs before they hatch, as chick-rearing is when peak food demand peaks. However, on ethical grounds it is likely to still be preferable to remove eggs at an early stage of development. The method used to destroy the eggs should be given careful consideration, and RSPB staff (whether on or off an RSPB reserve) must follow the RSPB Gull Control Code of Practice. Egg destruction is considered to be a form of lethal control and must always be done under the appropriate licence.

Gulls specialising in predating terns

Most predation of terns by adult large gulls appears to be by individual specialist gulls, and targeted removal of these individual gulls has a significant impact on predation levels (Guillemette and Brousseau 2001; Scopel & Diamond 2017). It is likely that colony managers will need to continue to make the case for targeted lethal control of individual gulls which specialise in predating terns, while remaining aware that this may be controversial and subject to the necessary licences. A population-level approach should be taken to the conservation of large gulls, actively protecting them at the key large gull colonies which contribute significantly to their populations.

Canes have also been trialled at a number of tern colonies as a way of reducing opportunistic predation attempts by large gulls and other avian predators.

Large gull species (in the UK and Ireland these are herring gull Larus argentatus, lesser black-backed gull Larus fuscus and great black-backed gull Larus marinus) can have an adverse effect on tern breeding colonies, either by predating or displacing terns. In the past, large gulls have sometimes been culled on nature reserves for conservation reasons, however most conservation land managers will want to minimise the use of lethal control methods as herring gulls is on the Red List and lesser black-backed and great black-backed gulls are on the Amber List in Birds of Conservation Concern 4 (Eaton et al. 2015).

One way of minimising the need to employ lethal control methods, is to keep areas free for breeding terns by preventing large gulls from attempting to breed using disturbance techniques. These are most effective in the pre-breeding period before birds set up territories, and before the terns arrive. However, studies have shown that large gulls will often habituate to disturbance over time and so disturbance is most effective when a suite of techniques is used and also when it is backed up with occasional lethal control (e.g. Cook et al. 2008).

It may still be necessary to remove large gull eggs and nests, especially where the aim is to prevent displacement of tern colonies. This is legally considered to be a form of lethal control and must be done under licence from the relevant statutory agency.

Targeted lethal control of individual gulls which specialise in predating tern nests or young is also likely to continue to be a necessary part of colony management, and again must be done under licence. Accurately identifying individual gulls is labour-intensive but necessary to ensure that this is kept to a minimum.

Colony managers will need to assess what is practical at each colony on a case-by-case basis and to continue to adapt the methods used as knowledge develops and as gulls change their behaviour or habituate to existing methods of management.

Disturbance Methods

A number of techniques have been trialled to deter large gulls from breeding on Coquet Island, Northumberland, which is managed by the RSPB. These were reviewed in Morrision & Allcorn (2006) and the most effective were those incorporating loud bangs (which could not be used in the breeding season because of the disturbance to other species, but were useful pre-breeding when only the large gulls were present), gull distress calls which were moderately effective and could be used at any time of year, and physical human presence.

Laser hazing has recently been trialled as a method of deterring large gulls and other avian predators at a number of tern colonies in the UK and Ireland, including Coquet Island, the Skerries, Rockabill and Hodbarrow and little tern colonies at Gronant, the Long Nanny and Chesil. Lasers to disperse birds are sold under the trade names Agrilaser (for crop protection) and Aerolaser (a more powerful and expensive model intended for use at airports). The laser is aimed at the ground and the laser ‘dot’ moved toward the bird; a process referred to as ‘hazing’. The manufacturer claims that birds perceive the dot as a threat and do not become habituated. RSPB trials of aerolasers are ongoing and it is too soon to assess effectiveness and habituation.

Anecdotal reports on the use of the laser to deter settlement suggest mixed success, as would be predicted by the manufacturers guidelines which suggest that the effective range is greatly reduced in strong light. The suppliers websites offer further information. On Rockabill an Agrilaser pointed at the unoccupied island of the Bill and moved around the areas where gulls were present was extremely effective in low light levels, causing gulls to take off almost immediately, but during daylight hours was ineffective apart from on extremely overcast or misty days (Rockabill Tern Report 2019). At Hodbarrow a laser was generally considered to be effective throughout the day, when used at relatively short range from a hide overlooking the tern breeding area (Dave Blackledge, RSPB Cumbria Coast, pers. com.). On Coquet Island the laser has been successful as a settlement deterrent (see case study), although the effectiveness has varied in different light conditions.

Some sites also attempted laser hazing to deter predation attempts, and preliminary analysis these results suggests that hazing reduced the probability of a predation attempt but that hazed predation attempts were more likely to be successful, perhaps indicating that a predator that is more certain of taking prey is less likely to be distracted.

Managing territorial large gulls

Often despite best efforts at discouraging large gulls from settling, a few will still attempt to nest in areas which are specifically manged for terns. Once established on a territory displacement methods are unlikely to work. At this point, if it is possible to do so without serious disturbance to other species, and subject to having the appropriate licence agreements, the only available measure is to remove nests and eggs. If the aim is to avoid displacement of terns (and if no gull census figure is required) then it is best to do this as soon as possible and continue monitoring, as territorial pairs will sometimes re-lay within the territory but in a new nest. If the aim is to minimise predation pressure, the key is to remove eggs before they hatch, as chick-rearing is when peak food demand peaks. However, on ethical grounds it is likely to still be preferable to remove eggs at an early stage of development. The method used to destroy the eggs should be given careful consideration, and RSPB staff (whether on or off an RSPB reserve) must follow the RSPB Gull Control Code of Practice. Egg destruction is considered to be a form of lethal control and must always be done under the appropriate licence.

Gulls specialising in predating terns

Most predation of terns by adult large gulls appears to be by individual specialist gulls, and targeted removal of these individual gulls has a significant impact on predation levels (Guillemette and Brousseau 2001; Scopel & Diamond 2017). It is likely that colony managers will need to continue to make the case for targeted lethal control of individual gulls which specialise in predating terns, while remaining aware that this may be controversial and subject to the necessary licences. A population-level approach should be taken to the conservation of large gulls, actively protecting them at the key large gull colonies which contribute significantly to their populations.

Canes have also been trialled at a number of tern colonies as a way of reducing opportunistic predation attempts by large gulls and other avian predators.

Published Research

Morrison and Allcorn (2006) described disturbance methods trialled on Coquet Island, while Booth and Morrison (2010) found that the disturbance regimes employed between 2000 and 2009 on Coquet Island successfully reduced the number of herring gulls and lesser black-backed gulls nesting (from approximately 250 pairs in 2002 to under 20 in 2009), a period in which the populations of four tern species increased.

Lavers et. al. (2010) reviewed 112 studies which report the observed demographic responses of bird populations to predator removal campaigns. The most commonly reported response was an increase in productivity, including in common terns Sterna hirundo after removal of ring-billed gulls Larus delawarensis and least terns Sternula antillarum after removal of multiple predators. Smaller and ground nesting birds were more likely to benefit.

Guillemette and Brousseau (2001) found that fledging success at a common tern colony in eastern Canada was higher in 1994 when specialist chick-predating gulls (four herring gulls and one great black-backed gull) were selectively shot, compared with 1993 and 1995, when no gulls were culled (16% of 115 eggs fledged vs. no chicks fledged from 165 eggs). Predation rates differed markedly amongst specialist predatory gulls, with one individual accounting for 85% of all successful attempts made during the baseline period. Once this gull was removed, the remaining predators increased their predation rate in a manner suggestive of a despotic system. Observations conducted in 1995 showed that the predation rate was almost zero at the beginning of the season but increased dramatically later in the summer, with two gulls together making about 60% of the captures. They concluded that culling predatory gulls can be an effective management tool to enhance productivity in sensitive or endangered species such as terns. However, targeted control would need to be repeated each year in order to provide protection over consecutive years.

Scopel & Diamond (2017) found that targeted lethal control of the tern specialist gulls was consistently more effective than non-lethal control. Of the tern species considered (Arctic Sterna paradisaea, common, least and roseate Sterna dougallii) in this case, Arctic terns were the most susceptible to predation and common terns the most resilient. Cessation of targeted lethal control lead to colony abandonment within 6 to 7 years (see also Scopel & Diamond 2018). A combination of targeted lethal control and non-lethal control (displacement) minimised the number of gulls removed.

Anderson and Devlin (1999) show how an abandoned tern colony was restored by killing herring and great black-backed gulls, but that continued immigration of these species from other colonies required ongoing management. Eider ducks benefitted from reduced predation of ducklings while black guillemot Cephalus grylle numbers increased substantially and Atlantic puffins Fratercla arctica colonised.

Kress (1983) and (1997) reports the use of extensive lethal gull control during the re-establishment of breeding tern colonies on islands in the Gulf of Maine. Culling on this scale was undoubtedly effective in freeing up habitat for recolonization by breeding terns but seems unlikely to be permitted in the UK at this point given the conservation status of most large gull species.

Morrison and Allcorn (2006) described disturbance methods trialled on Coquet Island, while Booth and Morrison (2010) found that the disturbance regimes employed between 2000 and 2009 on Coquet Island successfully reduced the number of herring gulls and lesser black-backed gulls nesting (from approximately 250 pairs in 2002 to under 20 in 2009), a period in which the populations of four tern species increased.

Lavers et. al. (2010) reviewed 112 studies which report the observed demographic responses of bird populations to predator removal campaigns. The most commonly reported response was an increase in productivity, including in common terns Sterna hirundo after removal of ring-billed gulls Larus delawarensis and least terns Sternula antillarum after removal of multiple predators. Smaller and ground nesting birds were more likely to benefit.

Guillemette and Brousseau (2001) found that fledging success at a common tern colony in eastern Canada was higher in 1994 when specialist chick-predating gulls (four herring gulls and one great black-backed gull) were selectively shot, compared with 1993 and 1995, when no gulls were culled (16% of 115 eggs fledged vs. no chicks fledged from 165 eggs). Predation rates differed markedly amongst specialist predatory gulls, with one individual accounting for 85% of all successful attempts made during the baseline period. Once this gull was removed, the remaining predators increased their predation rate in a manner suggestive of a despotic system. Observations conducted in 1995 showed that the predation rate was almost zero at the beginning of the season but increased dramatically later in the summer, with two gulls together making about 60% of the captures. They concluded that culling predatory gulls can be an effective management tool to enhance productivity in sensitive or endangered species such as terns. However, targeted control would need to be repeated each year in order to provide protection over consecutive years.

Scopel & Diamond (2017) found that targeted lethal control of the tern specialist gulls was consistently more effective than non-lethal control. Of the tern species considered (Arctic Sterna paradisaea, common, least and roseate Sterna dougallii) in this case, Arctic terns were the most susceptible to predation and common terns the most resilient. Cessation of targeted lethal control lead to colony abandonment within 6 to 7 years (see also Scopel & Diamond 2018). A combination of targeted lethal control and non-lethal control (displacement) minimised the number of gulls removed.

Anderson and Devlin (1999) show how an abandoned tern colony was restored by killing herring and great black-backed gulls, but that continued immigration of these species from other colonies required ongoing management. Eider ducks benefitted from reduced predation of ducklings while black guillemot Cephalus grylle numbers increased substantially and Atlantic puffins Fratercla arctica colonised.

Kress (1983) and (1997) reports the use of extensive lethal gull control during the re-establishment of breeding tern colonies on islands in the Gulf of Maine. Culling on this scale was undoubtedly effective in freeing up habitat for recolonization by breeding terns but seems unlikely to be permitted in the UK at this point given the conservation status of most large gull species.

Case Studies

Coquet Island, Northumberland: intensive large gull management to protect roseate terns

Coquet Island is managed by the RSPB for its nationally important populations of breeding seabirds including common tern, Arctic tern, Sandwich tern Sterna sandvicensis, roseate tern, black-headed gulls Chroicocephalus ridibundus and Atlantic puffins. It is the only regular breeding colony of roseate terns in the UK and the management of this site is critical to the conservation of this species in the UK.

The Coquet Island tern colonies are threatened by large gulls (lesser black-backed and herring gull) in both through predation and displacement. Predation of tern chicks, especially roseate terns could reduce recruitment and, if persistent, deter terns from breeding on the island in future. Partial displacement has occurred in the past when a big increase in the large gull population in 1976 pushed terns (which used to occupy sites around the island) into the area immediately around the lighthouse, a distribution pattern which persists to this day. Lethal control was undertaken from 1977 to 1984 reduce the number of large gulls breeding on the island, which then persisted at a relatively low level. There was a second rapid increase in large gull population in the late 1990s, so since 2000 a programme of work has been in place to protect the tern colonies. These rapid increases in large gull numbers are linked to displacement of large gulls from mainland sites.

Coquet Island, Northumberland: intensive large gull management to protect roseate terns

Coquet Island is managed by the RSPB for its nationally important populations of breeding seabirds including common tern, Arctic tern, Sandwich tern Sterna sandvicensis, roseate tern, black-headed gulls Chroicocephalus ridibundus and Atlantic puffins. It is the only regular breeding colony of roseate terns in the UK and the management of this site is critical to the conservation of this species in the UK.

The Coquet Island tern colonies are threatened by large gulls (lesser black-backed and herring gull) in both through predation and displacement. Predation of tern chicks, especially roseate terns could reduce recruitment and, if persistent, deter terns from breeding on the island in future. Partial displacement has occurred in the past when a big increase in the large gull population in 1976 pushed terns (which used to occupy sites around the island) into the area immediately around the lighthouse, a distribution pattern which persists to this day. Lethal control was undertaken from 1977 to 1984 reduce the number of large gulls breeding on the island, which then persisted at a relatively low level. There was a second rapid increase in large gull population in the late 1990s, so since 2000 a programme of work has been in place to protect the tern colonies. These rapid increases in large gull numbers are linked to displacement of large gulls from mainland sites.

The annual gull management on Coquet Island begins with a disturbance programme deploying techniques outlined in Morrison and Allcorn (2006) from mid-late March. This aims to minimise the number of large gull pairs establishing territories on Coquet. Once other species arrive, most disturbance techniques have to stop, but active human disturbance can continue where this will not affect other species.

In the breeding season, large gulls are controlled on Coquet under licence from Natural England (NE) by removing nests and eggs across most of the island to restrict nesting to the northeast end, as far as possible from the tern colonies. However, NE require that some large gulls nests are left. An ongoing PhD project on large gulls on Coquet indicates that leaving large gull nests laid early in the season (as opposed to re-laid nests later on), may reduce the impact on roseate terns as the peak food demand of early-laid large gull chicks corresponds with the presence of a large number of chicks of other tern and small gull species being available (I. Alfarwi pers. com.). Roseate terns often leave the island later than other tern and small gull species so are more vulnerable later in the season

There is permission to shoot individual large gulls which persistently predate roseate terns or take a larger number of common or Arctic terns, indicating a specialisation. An annual licence is obtained and reported against for this activity. All these measures are necessary because if large gull populations increase then there is a real possibility that all the tern species could ultimately be displaced from Coquet Island.

Hodbarrow, Cumbria, England: using a laser to keep islands available for terns

At Hodbarrow the tern breeding colony is on an island of iron mine slag in (see habitat creation). Historically, small numbers of lesser black-back gulls also bred on the island, but in 2007/2008 the number of breeding large gulls increased dramatically following their displacement from the roof of a nearby prison. By 2010, the little terns Sternula albifrons and common terns had deserted, while Sandwich terns and black-headed gulls were displaced to the colony margins and suffering heavy predation. The breeding large gulls were in turn discovered by foxes, which cleared out the colony. In 2016, an anti-predator fence was installed in the channel.

A trial of recorded lesser black-backed gull distress calls was not found to be effective, so in the last few years a laser has been used to discourage large gulls from settling from March 1 for two months and is stopping most large gulls from settling although a couple of pairs will still often try to nest. Early in the season targeted human disturbance by walking onto the island is also possible but by mid/late March breeding waders are on the island and human activity is limited to removing any large gull nests. There is permission to shoot individual large gulls which persistently predate terns.

At Hodbarrow the tern breeding colony is on an island of iron mine slag in (see habitat creation). Historically, small numbers of lesser black-back gulls also bred on the island, but in 2007/2008 the number of breeding large gulls increased dramatically following their displacement from the roof of a nearby prison. By 2010, the little terns Sternula albifrons and common terns had deserted, while Sandwich terns and black-headed gulls were displaced to the colony margins and suffering heavy predation. The breeding large gulls were in turn discovered by foxes, which cleared out the colony. In 2016, an anti-predator fence was installed in the channel.

A trial of recorded lesser black-backed gull distress calls was not found to be effective, so in the last few years a laser has been used to discourage large gulls from settling from March 1 for two months and is stopping most large gulls from settling although a couple of pairs will still often try to nest. Early in the season targeted human disturbance by walking onto the island is also possible but by mid/late March breeding waders are on the island and human activity is limited to removing any large gull nests. There is permission to shoot individual large gulls which persistently predate terns.

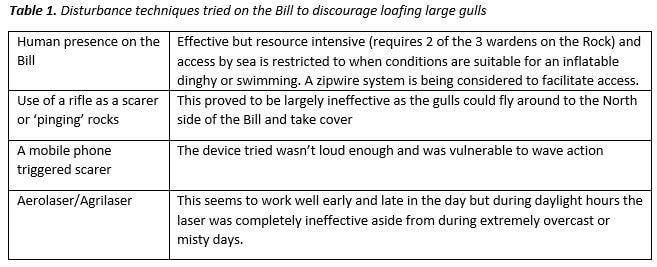

Rockabill, Ireland: managing loafing gulls predating seabird colonies

The Rockabill tern colony in the Irish sea is managed by BirdWatch Ireland and consists of two granite islands: the Rock, and the Bill. Wardens are resident on the Rock, while the Bill is currently only accessible by boat or by swimming when sea conditions allow.

Roseate, common, and a few Arctic terns breed on the Rock. Arctic terns and kittiwakes Rissa tridactyla nested on the Bill, but the Arctic terns have been largely displaced by loafing large gulls, which are also predating kittiwake nests meaning few young are fledged. In 2018, gulls began taking roseate tern eggs out of nest boxes on the Rock.

A few herring gulls try to build nests on the islands each season and the nests are destroyed, however, the number of loafing large gulls on the Bill can number over 500 (mainly great black-backed gulls but also some herring gulls). Various techniques have been tried to discourage loafing gulls on the Bill with mixed results.

The Rockabill tern colony in the Irish sea is managed by BirdWatch Ireland and consists of two granite islands: the Rock, and the Bill. Wardens are resident on the Rock, while the Bill is currently only accessible by boat or by swimming when sea conditions allow.

Roseate, common, and a few Arctic terns breed on the Rock. Arctic terns and kittiwakes Rissa tridactyla nested on the Bill, but the Arctic terns have been largely displaced by loafing large gulls, which are also predating kittiwake nests meaning few young are fledged. In 2018, gulls began taking roseate tern eggs out of nest boxes on the Rock.

A few herring gulls try to build nests on the islands each season and the nests are destroyed, however, the number of loafing large gulls on the Bill can number over 500 (mainly great black-backed gulls but also some herring gulls). Various techniques have been tried to discourage loafing gulls on the Bill with mixed results.

Extensive lethal control is not considered practicable and would be difficult to justify given the amber and red-listed status of great black-backed and herring gull respectively in Ireland. Minimising large gull predation on Rockabill is likely to be the single most significant management action that can be taken to increase breeding success and recruitment for roseate terns, common terns, Arctic terns and kittiwakes. A combination of multiple methods is likely to be needed.

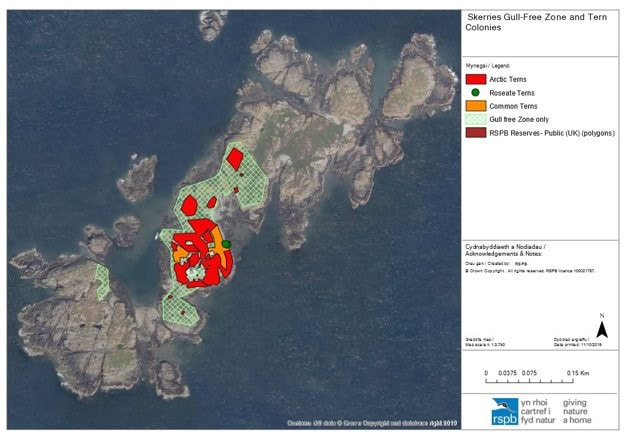

The Skerries, Wales: maintaining a gull-free zone for nesting terns

The Skerries are a group of rocky islands covering a total of 9 ha in the Irish Sea about 3 km north of the coast of Anglesey, North Wales. The site is managed by the RSPB as a nature reserve, with two residential wardens in the breeding season and no public access.

The Skerries are a group of rocky islands covering a total of 9 ha in the Irish Sea about 3 km north of the coast of Anglesey, North Wales. The site is managed by the RSPB as a nature reserve, with two residential wardens in the breeding season and no public access.

Since the mid-1990s the Skerries have seen breeding tern numbers grow from around 500 to over 4000 pairs, although numbers fell after a probable botulism outbreak in 2016. The site is one of the largest Arctic tern colonies in the UK and also supports breeding common terns (around 300 pairs), and small numbers of roseate terns breeding intermittently. In 2019, two roseate tern pairs and one mixed roseate/common tern pair bred on the Skerries. However, in 2020 under Covid-19 restrictions there were no wardens present and the tern colony deserted, thought to be a result of two juvenile peregrines Falco peregrinus roosting on the lighthouse.

The Skerries also supports nationally important breeding populations of herring gulls (up to 5% of the breeding population in Wales), and smaller numbers of lesser black-backed and great black-backed gulls. Observations show great black-backed gulls predate the nests of other two large gull species on Skerries.

To balance the competing conservation interests of the breeding terns and breeding gulls, the Skerries wardens maintain areas free of nesting gulls (see Figure 4). All nests and eggs of large gulls are removed within this zone, but elsewhere gulls are allowed to settle and breed.

Large gulls are deterred from entering the gull-free zone by scarecrows, noisemakers and human presence, particularly close to likely perches. This minimises the number of eggs and nests it is necessary to remove. An Agrilaser has been used with some success against gulls as well as ravens Corvus corax and carrion crows Corvus corone. A gull scarer playing distress calls was trialled but considered ineffective. There is consent to shooting individual large gulls, which are known to have taken 20 or more eggs, chicks, fledglings or adults persistently over a ten-day period.

Relevant sections of Conservation Evidence

Action: Control avian predators on islands

Action: Reduce inter-specific competition for nest sites of ground nesting seabirds by removing competitor species

Action: Control predators not on islands for seabirds

Useful Links

Aerolaser/agrilaser: https://www.birdcontrolgroup.com/deter-birds-manually/

Action: Control avian predators on islands

Action: Reduce inter-specific competition for nest sites of ground nesting seabirds by removing competitor species

Action: Control predators not on islands for seabirds

Useful Links

Aerolaser/agrilaser: https://www.birdcontrolgroup.com/deter-birds-manually/

References

Anderson J.G.T. and Devlin C.M. (1999) Restoration of a multi-species seabird colony. Biological Conservation 90 175-181

Booth V. & Morrison P. (2010) Effectiveness of disturbance methods and egg removal to deter large gulls Larus spp. from competing with nesting terns Sterna spp. on Coquet Island RSPB reserve, Northumberland, England. Conservation Evidence, 7, 39-43

Cook A., Rushton S., Allan J. and Baxtern A. (2008) An Evaluation of Techniques to Control Problem Bird Species on Landfill Sites. Environmental Management 41: 834–843

Eaton, M., Aebischer, N., Brown, A., Hearn, R., Lock, L., Musgrove, A., Noble, D., Stroud, D. & Gregory, R. (2015). Birds of Conservation Concern 4: the population status of birds in the UK, Channel Islands and Isle of Man. British Birds. 108. 708-746.

Guillemette M. and Brousseau P. (2001) Does culling of predatory gulls enhance the productivity of breeding common terns? Journal of Applied Ecology, 38, 1-8

Kress, S.W. (1983) The use of decoys, sound recordings, and gull control for re-establishing a tern colony in Maine. Colonial Waterbirds 6: 185–196.

Kress, S.W. (1997) Using animal behaviour for conservation: case studies in seabird restoration from the Maine coast, USA. Journal of the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology 29(1): 1–26.

Lavers, J.L., Wilcox, C. & Josh Donlan, C. (2010). Bird demographic responses to predator removal programs. Biological Invasions 12, 3839–3859.

Morrison P. & Allcorn R.I. (2006) The effectiveness of different methods to deter large gulls Larus spp. from competing with nesting terns Sterna spp. on Coquet Island RSPB reserve, Northumberland, England. Conservation Evidence, 3, 84-87

Scopel, L.C. & Diamond, A.W. (2017) The case for lethal control of gulls on seabird colonies. Journal of Wildlfe Management, 81: 572-580.

Scopel, L.C., & Diamond, A.W. (2018). Predation and food–weather interactions drive colony collapse in a managed metapopulation of Arctic Terns (Sterna paradisaea). Canadian Journal of Zoology. 96 (1) 13-22

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Paul Morrison (RSPB Coquet Island), Dave Blackledge (RSPB Cumbria Coast), Craig Edwards (RSPB Dungeness), Daniel Hayhow (RSPB Conservation Science), David Steel (Scottish Natural Heritage) and Steve Newton (Birdwatch Ireland).

Anderson J.G.T. and Devlin C.M. (1999) Restoration of a multi-species seabird colony. Biological Conservation 90 175-181

Booth V. & Morrison P. (2010) Effectiveness of disturbance methods and egg removal to deter large gulls Larus spp. from competing with nesting terns Sterna spp. on Coquet Island RSPB reserve, Northumberland, England. Conservation Evidence, 7, 39-43

Cook A., Rushton S., Allan J. and Baxtern A. (2008) An Evaluation of Techniques to Control Problem Bird Species on Landfill Sites. Environmental Management 41: 834–843

Eaton, M., Aebischer, N., Brown, A., Hearn, R., Lock, L., Musgrove, A., Noble, D., Stroud, D. & Gregory, R. (2015). Birds of Conservation Concern 4: the population status of birds in the UK, Channel Islands and Isle of Man. British Birds. 108. 708-746.

Guillemette M. and Brousseau P. (2001) Does culling of predatory gulls enhance the productivity of breeding common terns? Journal of Applied Ecology, 38, 1-8

Kress, S.W. (1983) The use of decoys, sound recordings, and gull control for re-establishing a tern colony in Maine. Colonial Waterbirds 6: 185–196.

Kress, S.W. (1997) Using animal behaviour for conservation: case studies in seabird restoration from the Maine coast, USA. Journal of the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology 29(1): 1–26.

Lavers, J.L., Wilcox, C. & Josh Donlan, C. (2010). Bird demographic responses to predator removal programs. Biological Invasions 12, 3839–3859.

Morrison P. & Allcorn R.I. (2006) The effectiveness of different methods to deter large gulls Larus spp. from competing with nesting terns Sterna spp. on Coquet Island RSPB reserve, Northumberland, England. Conservation Evidence, 3, 84-87

Scopel, L.C. & Diamond, A.W. (2017) The case for lethal control of gulls on seabird colonies. Journal of Wildlfe Management, 81: 572-580.

Scopel, L.C., & Diamond, A.W. (2018). Predation and food–weather interactions drive colony collapse in a managed metapopulation of Arctic Terns (Sterna paradisaea). Canadian Journal of Zoology. 96 (1) 13-22

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Paul Morrison (RSPB Coquet Island), Dave Blackledge (RSPB Cumbria Coast), Craig Edwards (RSPB Dungeness), Daniel Hayhow (RSPB Conservation Science), David Steel (Scottish Natural Heritage) and Steve Newton (Birdwatch Ireland).