Citation: Babcock and Booth (2020) Habitat: Creation and Restoration. Tern Conservation Best Practice. Produced for “Improving the conservation prospects of the priority species roseate tern throughout its range in the UK and Ireland” LIFE14 NAT/UK/000394’

Last updated: October 2020

This is a live document we update regularly. If you have comments and suggestions, please email Chantal.Macleod-Nolan@rspb.org.uk

Last updated: October 2020

This is a live document we update regularly. If you have comments and suggestions, please email Chantal.Macleod-Nolan@rspb.org.uk

| Babcock and Booth (2020) Habitat: Creation and Restoration. Tern Conservation Best Practice. | |

| File Size: | 3884 kb |

| File Type: | |

Key Messages

- Habitat restoration and the creation of new habitat will become increasingly important for tern conservation as the amount natural breeding habitat available to tern declines. See also Vegetation Management.

- Design of restoration and creation projects depends on the ecological requirements of the species intended to benefit but can incorporate practical elements to enable future management.

- Dredgings are an under-used resource in the UK, but elsewhere in the world ‘beneficial use’ of dredgings is the norm.

- Many of the best examples of tern habitat restoration and creation come from conservation practitioners, and a selection of these, covering a variety of scenarios, is provided in the case studies.

Information

The constraint of natural coastal processes by hard coastal defences and exacerbated by sea-level rise, the development of the coastline (Schippers et al. 2009), and recreational disturbance have all contributed to the loss of tern nesting habitat, which is not being offset by the natural creation of new sites. However, terns will readily adopt artificially created habitats provided their requirements are met, and previously occupied sites which have become unsuitable for terns can be restored and recolonised.

Small-scale tern breeding habitat creation or restoration projects can play a valuable role in contributing to a network of tern breeding sites. Landscape scale projects, such as managed realignment of coastlines can provide opportunities to create larger areas of new habitat, in which is it important to ensure the value of tern nesting habitat is recognised alongside, for example, targets for compensatory habitats.

For any potential tern habitat creation or restoration, it is important to consider:

The required lifespan of the habitat is a decision specific to each individual project. However, if there is no locally available food source, then habitat which is otherwise perfect will not support a successful tern colony. Little terns Sternula albifrons feed primarily within 4km of the colony, often much closer especially during chick-rearing (Parsons et al. 2015). Common terns Sterna hirundo and roseate terns Sterna dougallii forage up to maximum of 15-19km of the colony while Arctic Sterna paradisaea and Sandwich terns Thalasseus sandvicensis forage up to 33km (Wilson et al. 2015); these are mean maximum figures from a number of different colonies, and in many cases, foraging will be much closer. Common terns will also forage in fresh water, meaning this is the only UK tern species which regularly occurs at inland sites. If there are terns already feeding in an area within foraging range of the relevant species this is an indication that any new colony will have food available.

Restoration

Former tern colonies are most likely to have been abandoned due to the habitat becoming unsuitable (e.g. vegetation succession) or following breeding failures, often caused by flooding, predation or disturbance. The key to restoration is identifying and rectifying the issues. This may be as simple as vegetation management or may require land forming (see Blue Circle Island case study), or anti-predator measures and visitor management.

Whether creating or restoring habitats, most UK tern species select nest sites with an open aspect and a substrate of unvegetated or sparsely vegetated gravel or shingle. Short grass swards are also used by some colonies, and roseate terns will also use more vegetated sites, nesting under grass tussocks or other vegetation or using abandoned burrows for shelter.

Creation

Expect that planning, designing and obtaining the relevant permissions for a habitat creation project could take several years, depending on the scale of the project. The design details will depend on the species and the situation. Densely colonial species such as Sandwich terns tend to prefer larger islands for nesting. Smaller tern species will use smaller sites but also benefit from islands sufficiently large to hold a colony big enough to defend itself from predators. Little terns usually nest at lower density, so will occupy a relatively large area for the size of the colony. The preference for an open aspect means low, flat islands are often best for terns. If these are positioned at a height where they are submerged by winter water levels but exposed before for prospecting birds arrive in spring, this brings the added benefit of natural vegetation control, reducing maintenance time and costs.

When designing islands in larger and deeper water bodies, take account of the prevailing wind direction the associated fetch, and therefore the expected impact of erosion. If the side exposed to erosion is not visible, or if a natural aesthetic is not a consideration, then it could be reinforced with gabions filled with stones.

If it is anticipated that mammalian predation will be an issue, the intended route of anti-predator fencing should be incorporated into the design, even if the fence is not installed until later. This provides an opportunity to minimise the number of weak points in the fence by avoiding crossing landscape features such as ditches, avoiding topographic variation, and minimising the number of access gates.

Access routes can sometimes also be incorporated into the design. For example, where water levels do not fluctuate too dramatically a lagoon island can sometimes be reached by a submerged causeway, removing the need for a boat. A causeway needs a firm substrate and it may be advisable to mark out the position on the ground to make it easier to find and safe to use (but avoid creating predator perches near the tern colony).

If the habitat creation involves working with contractors, ensure a detailed specification and work closely with them especially if the construction team do not have conservation experience. Many machinery operators are used to being asked to create straight lines rather than naturalistic contours.

Ongoing management should be included in the project planning and site budgeting. For example, most little tern colonies on publicly accessible sites require fencing, wardening and signage to limit predation and human disturbance, representing a substantial long-term commitment. Even less demanding nesting habitats are likely to require occasional vegetation management.

Once completed, and especially before vegetation has re-established chick shelters should be provided for shelter from the elements and predators. Decoys and lures may be used to attract terns to areas of safe, suitable nesting habitat.

For a list of considerations before commencing a habitat creation project see the checklist in Appendix 1.

The constraint of natural coastal processes by hard coastal defences and exacerbated by sea-level rise, the development of the coastline (Schippers et al. 2009), and recreational disturbance have all contributed to the loss of tern nesting habitat, which is not being offset by the natural creation of new sites. However, terns will readily adopt artificially created habitats provided their requirements are met, and previously occupied sites which have become unsuitable for terns can be restored and recolonised.

Small-scale tern breeding habitat creation or restoration projects can play a valuable role in contributing to a network of tern breeding sites. Landscape scale projects, such as managed realignment of coastlines can provide opportunities to create larger areas of new habitat, in which is it important to ensure the value of tern nesting habitat is recognised alongside, for example, targets for compensatory habitats.

For any potential tern habitat creation or restoration, it is important to consider:

- the likely impact of natural coastal processes and sustainability of the site

- the height of spring tides or water level fluctuations

- local food availability within the foraging range of the relevant species

- predation threats and how these will be managed

- risk of human disturbance and how this will be managed

- whether biosecurity measures will be required to protect any colony

- cost of works and subsequent maintenance

The required lifespan of the habitat is a decision specific to each individual project. However, if there is no locally available food source, then habitat which is otherwise perfect will not support a successful tern colony. Little terns Sternula albifrons feed primarily within 4km of the colony, often much closer especially during chick-rearing (Parsons et al. 2015). Common terns Sterna hirundo and roseate terns Sterna dougallii forage up to maximum of 15-19km of the colony while Arctic Sterna paradisaea and Sandwich terns Thalasseus sandvicensis forage up to 33km (Wilson et al. 2015); these are mean maximum figures from a number of different colonies, and in many cases, foraging will be much closer. Common terns will also forage in fresh water, meaning this is the only UK tern species which regularly occurs at inland sites. If there are terns already feeding in an area within foraging range of the relevant species this is an indication that any new colony will have food available.

Restoration

Former tern colonies are most likely to have been abandoned due to the habitat becoming unsuitable (e.g. vegetation succession) or following breeding failures, often caused by flooding, predation or disturbance. The key to restoration is identifying and rectifying the issues. This may be as simple as vegetation management or may require land forming (see Blue Circle Island case study), or anti-predator measures and visitor management.

Whether creating or restoring habitats, most UK tern species select nest sites with an open aspect and a substrate of unvegetated or sparsely vegetated gravel or shingle. Short grass swards are also used by some colonies, and roseate terns will also use more vegetated sites, nesting under grass tussocks or other vegetation or using abandoned burrows for shelter.

Creation

Expect that planning, designing and obtaining the relevant permissions for a habitat creation project could take several years, depending on the scale of the project. The design details will depend on the species and the situation. Densely colonial species such as Sandwich terns tend to prefer larger islands for nesting. Smaller tern species will use smaller sites but also benefit from islands sufficiently large to hold a colony big enough to defend itself from predators. Little terns usually nest at lower density, so will occupy a relatively large area for the size of the colony. The preference for an open aspect means low, flat islands are often best for terns. If these are positioned at a height where they are submerged by winter water levels but exposed before for prospecting birds arrive in spring, this brings the added benefit of natural vegetation control, reducing maintenance time and costs.

When designing islands in larger and deeper water bodies, take account of the prevailing wind direction the associated fetch, and therefore the expected impact of erosion. If the side exposed to erosion is not visible, or if a natural aesthetic is not a consideration, then it could be reinforced with gabions filled with stones.

If it is anticipated that mammalian predation will be an issue, the intended route of anti-predator fencing should be incorporated into the design, even if the fence is not installed until later. This provides an opportunity to minimise the number of weak points in the fence by avoiding crossing landscape features such as ditches, avoiding topographic variation, and minimising the number of access gates.

Access routes can sometimes also be incorporated into the design. For example, where water levels do not fluctuate too dramatically a lagoon island can sometimes be reached by a submerged causeway, removing the need for a boat. A causeway needs a firm substrate and it may be advisable to mark out the position on the ground to make it easier to find and safe to use (but avoid creating predator perches near the tern colony).

If the habitat creation involves working with contractors, ensure a detailed specification and work closely with them especially if the construction team do not have conservation experience. Many machinery operators are used to being asked to create straight lines rather than naturalistic contours.

Ongoing management should be included in the project planning and site budgeting. For example, most little tern colonies on publicly accessible sites require fencing, wardening and signage to limit predation and human disturbance, representing a substantial long-term commitment. Even less demanding nesting habitats are likely to require occasional vegetation management.

Once completed, and especially before vegetation has re-established chick shelters should be provided for shelter from the elements and predators. Decoys and lures may be used to attract terns to areas of safe, suitable nesting habitat.

For a list of considerations before commencing a habitat creation project see the checklist in Appendix 1.

Dredged Materials

In the UK, dredged materials are an under-utilised resource for habitat creation or restoration projects. Approximately 40-50 million m3 of sediment is dredged from ports and harbours around the UK each year, the vast majority of which is disposed of at sea as a waste product.

Other countries around the world make better use of dredged material, including to recharge and restore coastal habitats. This technique, referred to as ‘beneficial use’ accounts for only with around 1% of the material dredged each year in the UK. An RSPB report found that key issues limiting the amount of beneficial use in the UK include a licensing process that is difficult to navigate and isn’t supporting beneficial use, a lack of communication about opportunities leading to difficulties coordinating supply and demand, and the added costs that can be associated with delivering beneficial use projects compared to disposal at sea. Better recognition and implementation of the natural capital approach to fund beneficial use schemes, better strategic oversight and coordination of opportunities through the policy and planning framework and the use of databases to match supply and demand would help improve this situation. For a full consideration of this subject see Ausden et al. (2018)

In the UK, dredged materials are an under-utilised resource for habitat creation or restoration projects. Approximately 40-50 million m3 of sediment is dredged from ports and harbours around the UK each year, the vast majority of which is disposed of at sea as a waste product.

Other countries around the world make better use of dredged material, including to recharge and restore coastal habitats. This technique, referred to as ‘beneficial use’ accounts for only with around 1% of the material dredged each year in the UK. An RSPB report found that key issues limiting the amount of beneficial use in the UK include a licensing process that is difficult to navigate and isn’t supporting beneficial use, a lack of communication about opportunities leading to difficulties coordinating supply and demand, and the added costs that can be associated with delivering beneficial use projects compared to disposal at sea. Better recognition and implementation of the natural capital approach to fund beneficial use schemes, better strategic oversight and coordination of opportunities through the policy and planning framework and the use of databases to match supply and demand would help improve this situation. For a full consideration of this subject see Ausden et al. (2018)

Published Research

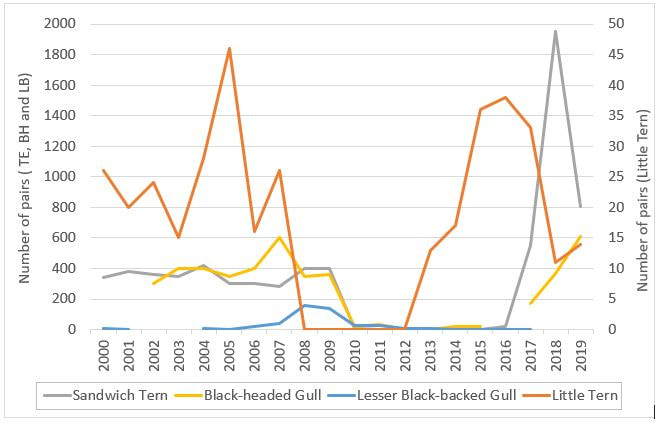

Akers & Allcorn (2006) documented the reprofiling of islands at the former Burrowes gravel pit, part of the RSPB reserve at Dungeness, Kent, England. The islands had supported up to 350 pairs of Sandwich tern, 300 pairs of common tern and more than 1,000 black-headed gulls Chroicocephalus ridibundus in the 1980s, but declined through the 1990s until there were no breeding terns by 2002. This was a result of falling water levels in the aquifer meaning that islands designed to be flooded in winter to manage vegetation were now dry throughout the year allowing woody vegetation to develop and the shingle to become covered by a thick humic layer. In 2005, the vegetation was removed and the islands were reprofiled to be lower so that they would be flooded over winter. This work was accomplished by floating an excavator and dumper out to the islands on a barge.

In the first year after the reprofiling one pair of common terns and five pairs of black-headed gulls returned to the islands, but so did nearly 100 pairs of herring gulls Larus argentatus. This may have discouraged the terns from returning, or it may be that the terns which had previously bred at Dungeness had relocated and bred successfully elsewhere.

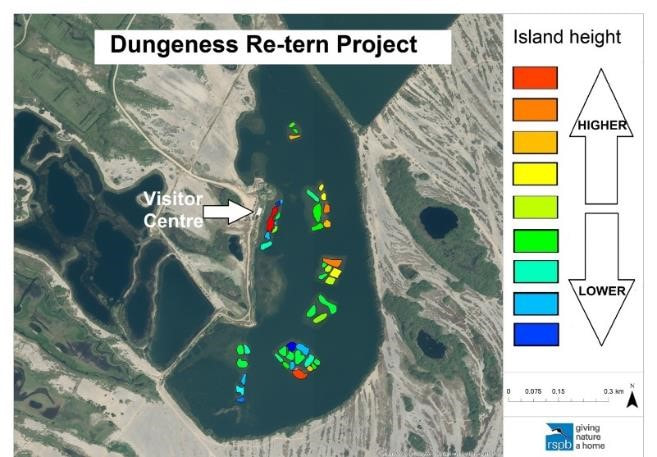

As an addendum to this paper: in the mid-2010 the aquifer level had risen again, likely due to a change in management by the water company. This meant that the lowered islands were now flooded until too late into the breeding season to be available to breeding birds. The Dungeness re-tern project was developed to float a JCB out and raise the islands following a carefully worked-out plan providing different island heights and profiles to be exposed as water levels fluctuate.

Akers & Allcorn (2006) documented the reprofiling of islands at the former Burrowes gravel pit, part of the RSPB reserve at Dungeness, Kent, England. The islands had supported up to 350 pairs of Sandwich tern, 300 pairs of common tern and more than 1,000 black-headed gulls Chroicocephalus ridibundus in the 1980s, but declined through the 1990s until there were no breeding terns by 2002. This was a result of falling water levels in the aquifer meaning that islands designed to be flooded in winter to manage vegetation were now dry throughout the year allowing woody vegetation to develop and the shingle to become covered by a thick humic layer. In 2005, the vegetation was removed and the islands were reprofiled to be lower so that they would be flooded over winter. This work was accomplished by floating an excavator and dumper out to the islands on a barge.

In the first year after the reprofiling one pair of common terns and five pairs of black-headed gulls returned to the islands, but so did nearly 100 pairs of herring gulls Larus argentatus. This may have discouraged the terns from returning, or it may be that the terns which had previously bred at Dungeness had relocated and bred successfully elsewhere.

As an addendum to this paper: in the mid-2010 the aquifer level had risen again, likely due to a change in management by the water company. This meant that the lowered islands were now flooded until too late into the breeding season to be available to breeding birds. The Dungeness re-tern project was developed to float a JCB out and raise the islands following a carefully worked-out plan providing different island heights and profiles to be exposed as water levels fluctuate.

Case Studies

RSPB Langstone Harbour, England: recharge of shingle-capped islands

The little tern population at Langstone Harbour on the south coast peaked at 171 pairs in 1989 but declined to a low point of 23 pairs in 2013. The decline appears to have been driven by repeated nest failures or low productivity due to tidal surges washing away eggs/young chicks, and predation by foxes reaching the islands at low tide. Other issues included decreasing habitat availability due to competition with other species (especially black-headed gulls) and erosion of habitat in increased winter storms.

The protected habitats in the harbour include the littoral mud and the saltmarsh vegetation, so no new islands could be created, nor existing ones extended. Langstone Harbour Little Tern Project therefore aimed to replenish the shingle caps on the islands in the little terns’ preferred nesting areas. Funding was sought and gratefully received from the EU Interreg fund, the Heritage Lottery Fund and Veolia. Permission to carry out the work was received from the relevant statutory organisations including Natural England, The Marine Management Organisation and The Langstone Harbour Board.

Langstone Harbour is an important wildfowl wintering site and so large-scale operations were ruled out before mid-February due to the disturbance impact. This left a window of opportunity of approximately two months before mid-April when the terns return. It was also necessary to work on spring tides as this was the only time that the depth of water around the islands was sufficient to float in materials, which meant that only two attempts were possible each spring.

The protected habitats necessitated very specific placement of shingle, so bulk bags were used for each load rather than moving materials in larger quantities.

The operations plan for each site could be broken down into the following steps:

The shingle at the little tern nesting sites was raised by 1-1.5m and extended to areas where the shingle was previously unsuitable.

RSPB Langstone Harbour, England: recharge of shingle-capped islands

The little tern population at Langstone Harbour on the south coast peaked at 171 pairs in 1989 but declined to a low point of 23 pairs in 2013. The decline appears to have been driven by repeated nest failures or low productivity due to tidal surges washing away eggs/young chicks, and predation by foxes reaching the islands at low tide. Other issues included decreasing habitat availability due to competition with other species (especially black-headed gulls) and erosion of habitat in increased winter storms.

The protected habitats in the harbour include the littoral mud and the saltmarsh vegetation, so no new islands could be created, nor existing ones extended. Langstone Harbour Little Tern Project therefore aimed to replenish the shingle caps on the islands in the little terns’ preferred nesting areas. Funding was sought and gratefully received from the EU Interreg fund, the Heritage Lottery Fund and Veolia. Permission to carry out the work was received from the relevant statutory organisations including Natural England, The Marine Management Organisation and The Langstone Harbour Board.

Langstone Harbour is an important wildfowl wintering site and so large-scale operations were ruled out before mid-February due to the disturbance impact. This left a window of opportunity of approximately two months before mid-April when the terns return. It was also necessary to work on spring tides as this was the only time that the depth of water around the islands was sufficient to float in materials, which meant that only two attempts were possible each spring.

The protected habitats necessitated very specific placement of shingle, so bulk bags were used for each load rather than moving materials in larger quantities.

The operations plan for each site could be broken down into the following steps:

- A hopper barge was loaded nearby with 850kg bulk bags of shingle

- At high tide on the beginning of the spring tide cycle, the hopper barge was bought as close to the site as possible with a second barge containing a static crane and 360o excavator alongside.

- The excavator was offloaded and positioned on the work site.

- The crane was used to take bags from the hopper barge and offload them on the island.

- The excavator placed the bulk bags exactly as required before upending them to release the shingle.

- Once operations began, they could work through the tidal cycle until complete (the hopper barge leaving at high tide to reload and then returning on the next high).

- When works were completed (which had to be before the end of the spring tide cycle to prevent getting stuck), the excavator was reloaded, and the barges drawn back to the main channel from which they could safely navigate.

The shingle at the little tern nesting sites was raised by 1-1.5m and extended to areas where the shingle was previously unsuitable.

Due to the short operational window, the decision was made to work on one island each year: South Binness in 2013 and Bakers Island in 2014. In both years poor weather had potential to delay the works but luckily the storms passed through quickly and only hours or days were lost.

The work on South Binness in 2013 took place on two spring tide cycles between early March and early April. The only major issue was a broken track on the excavator which caused a substantial delay. The little terns came back late that year but virtually all pairs nested on the recharge area as hoped.

The 2014 work on Bakers Island was affected by the winter storms that changed the morphology of the beach, with much of the shingle having been stripped away leaving mud. When operations began on the first spring tide cycle in early March working on the mud caused problems, but this was overcome on the second spring tide cycle (late March/early April) with the use of heavy-duty timber matting.

In both cases, once the shingle was placed in the desired locations, crushed cockle shells were spread over the areas to give them a naturalised feel and increase the attractiveness to little terns. Electric fences were erected around each site for the duration of the breeding season.

Results: approximately 2500m² of shingle habitat was restored over both islands with the average rise in island profile height being around 1m. The habitat created was very attractive to little terns with the South Binness recharge area being the main colony site in 2013 (19 out of 22 pairs settled there) and the colony being almost evenly divided between both sites after the 2014 work on Baker Island.

The Langstone Harbour little tern colony had one of its most productive years in 2014 with all the recorded chicks fledging from the restored shingle areas. This was in marked contrast to the previous three years which in total had seen only one chick fledge.

In 2015, storms (but not overwash) caused the failure of all but 7 little tern nests at Langstone and in 2016 only 11 pairs attempting to breed in the area and no chicks fledged. But in 2017 an estimated 36 pairs of birds managed to raise and fledge 27 chicks, and both primary little tern nesting sites in the harbour remain above the potential reach of all but the most devastating summer storm surges.

The work on South Binness in 2013 took place on two spring tide cycles between early March and early April. The only major issue was a broken track on the excavator which caused a substantial delay. The little terns came back late that year but virtually all pairs nested on the recharge area as hoped.

The 2014 work on Bakers Island was affected by the winter storms that changed the morphology of the beach, with much of the shingle having been stripped away leaving mud. When operations began on the first spring tide cycle in early March working on the mud caused problems, but this was overcome on the second spring tide cycle (late March/early April) with the use of heavy-duty timber matting.

In both cases, once the shingle was placed in the desired locations, crushed cockle shells were spread over the areas to give them a naturalised feel and increase the attractiveness to little terns. Electric fences were erected around each site for the duration of the breeding season.

Results: approximately 2500m² of shingle habitat was restored over both islands with the average rise in island profile height being around 1m. The habitat created was very attractive to little terns with the South Binness recharge area being the main colony site in 2013 (19 out of 22 pairs settled there) and the colony being almost evenly divided between both sites after the 2014 work on Baker Island.

The Langstone Harbour little tern colony had one of its most productive years in 2014 with all the recorded chicks fledging from the restored shingle areas. This was in marked contrast to the previous three years which in total had seen only one chick fledge.

In 2015, storms (but not overwash) caused the failure of all but 7 little tern nests at Langstone and in 2016 only 11 pairs attempting to breed in the area and no chicks fledged. But in 2017 an estimated 36 pairs of birds managed to raise and fledge 27 chicks, and both primary little tern nesting sites in the harbour remain above the potential reach of all but the most devastating summer storm surges.

RSPB Dungeness Re-Tern Project: island restoration by reforming shingle islands

Following the changes documented by Akers & Allcorn (2006) an increase in ground water level thought to be a result of changing management of the aquifer meant that the islands in Burrowes Pit remained flooded too late into the breeding season to be available to birds. An ambitious project was developed to raise island heights by floating a JCB out on a raft and scraping spare material from the sides of the gravel columns to build up the island height. The island heights were varied so that islands are sequentially exposed, particularly important in this case as there is no water level control on the reserve due to the highly porous nature of the shingle substrate. Working closely with the contractor also produced a complex micro-topography on each island, taking into account the likely viewing positions. Varied substrates were also used, providing habitat for the specialist damp sand plants and invertebrates at the reserve, as well as breeding and loafing birds.

Following the changes documented by Akers & Allcorn (2006) an increase in ground water level thought to be a result of changing management of the aquifer meant that the islands in Burrowes Pit remained flooded too late into the breeding season to be available to birds. An ambitious project was developed to raise island heights by floating a JCB out on a raft and scraping spare material from the sides of the gravel columns to build up the island height. The island heights were varied so that islands are sequentially exposed, particularly important in this case as there is no water level control on the reserve due to the highly porous nature of the shingle substrate. Working closely with the contractor also produced a complex micro-topography on each island, taking into account the likely viewing positions. Varied substrates were also used, providing habitat for the specialist damp sand plants and invertebrates at the reserve, as well as breeding and loafing birds.

Within a month of completion in September 2017, the 45 islands were already being used by over 500 oystercatchers Haematopus ostralegus and five spoonbills Platalea leucorodia and increasing numbers of lapwings Vanellus vanellus and golden plovers Pluvialis apricaria. The following breeding season the number of pairs of common terns breeding on the reserve (previously dependent on rafts) increased from 28 to 72 and has continued to increase since. The spectacle for visitors, including the sound of a tern colony on the approach to the Visitor Centre, has been greatly enhanced.

RSPB Larne Lough: Blue Circle Island, Northern Ireland: restoring an island by preventing flooding

Blue Circle Island (about 0.6 ha) was artificially created through depositing quarry spoil from Magheramorne Quarry by Blue Circle Cement (now Tarmac) working in partnership with the RSPB. Initial construction work in the early 1980s suffered from settling, but the island was eventually completed in 1990 and consisted of placing a ring of basalt blocks on the (shallow) seabed to above the mean high-water mark, before lining with a heavy geotextile, and infilling with two materials that were locally available in large amounts: dredged seabed sediment and inert kiln dust. After a year of further settling the north-west corner was identified as needing further attention. This area and the gradually lowering local perimeter of the island remained the primary areas of concern ever since and at high tides water passed through the north-west corner and overtopped the perimeter, flooding and eroding parts of the interior of the island. In addition, heavy vegetation growth led to increased numbers of black-headed gulls and Sandwich terns, while numbers of common and associated roseate terns declined.

Blue Circle Island (about 0.6 ha) was artificially created through depositing quarry spoil from Magheramorne Quarry by Blue Circle Cement (now Tarmac) working in partnership with the RSPB. Initial construction work in the early 1980s suffered from settling, but the island was eventually completed in 1990 and consisted of placing a ring of basalt blocks on the (shallow) seabed to above the mean high-water mark, before lining with a heavy geotextile, and infilling with two materials that were locally available in large amounts: dredged seabed sediment and inert kiln dust. After a year of further settling the north-west corner was identified as needing further attention. This area and the gradually lowering local perimeter of the island remained the primary areas of concern ever since and at high tides water passed through the north-west corner and overtopped the perimeter, flooding and eroding parts of the interior of the island. In addition, heavy vegetation growth led to increased numbers of black-headed gulls and Sandwich terns, while numbers of common and associated roseate terns declined.

Figure 8. Moving material onto Blue Circle Island (Daniel Piec; RSPB)

Figure 8. Moving material onto Blue Circle Island (Daniel Piec; RSPB)

As part of the Roseate Tern LIFE Project, the RSPB identified Blue Circle Island as a priority site for restoration in preparation for a potential expansion of roseate terns from the core strongholds. It has good food resources and had supported regular roseate tern breeding attempts. Rockabill (the largest colony in Europe) is not far from Larne Lough. There was also a colony of common terns, which roseate terns often associate with, as well as the assemblage of Sandwich terns and black-headed gulls. Funding was secured for the restoration of the island including:

The restoration project also included predator fencing, vegetation control, biosecurity monitoring and additional wardening.

Planning the work took 18 months and included the obtaining of a marine construction licence, a planning application (supported by detailed plans, Habitat Regulation Assessment, Ornithological Assessment and surveys) and a tender process. Construction in the autumn of autumn 2018 took about three weeks, with materials transported from the quay by barge and then moved onto the island itself by a platform-based digger. The total budget was in the region of £400,000.

In 2019, 2453 black-headed gull nests, 988 Sandwich tern nests, 166 common tern nests and a pair of roseate terns nested, and although vegetation still impaired monitoring efforts, at least one of the two roseate tern chicks is thought to have fledged.

- mending the breach in the sea wall in the south-west corner to prevent regular tidal flow in and out

- raising the level of the western perimeter to prevent overtopping at high tides

- raising the level of the interior of the island, where it has been eroded away, to a height above regular inundation (to replace lost material and ensure safety for breeding even in the event of some continued seepage of water into/onto the island).

The restoration project also included predator fencing, vegetation control, biosecurity monitoring and additional wardening.

Planning the work took 18 months and included the obtaining of a marine construction licence, a planning application (supported by detailed plans, Habitat Regulation Assessment, Ornithological Assessment and surveys) and a tender process. Construction in the autumn of autumn 2018 took about three weeks, with materials transported from the quay by barge and then moved onto the island itself by a platform-based digger. The total budget was in the region of £400,000.

In 2019, 2453 black-headed gull nests, 988 Sandwich tern nests, 166 common tern nests and a pair of roseate terns nested, and although vegetation still impaired monitoring efforts, at least one of the two roseate tern chicks is thought to have fledged.

Bird Island, Massachusetts, USA: raising, reinforcing and restoring an island

Bird Island is a small (c.0.8 hectare) island in Buzzards Bay, which supports important numbers of roseate and common terns. It has been intensively managed for terns since the late 1960s by the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife (MassWildlife).

The low island consists mainly of eroded glacial till protected by a riprap seawall originally built in the 1830s; it is exposed to wave action from the southwest and washed over in severe storms. The original revetment was built with a vertical face which had become damaged and the island eroded over the years. Low lying areas became salt marsh and were no longer suitable for tern nesting. By 2012 the amount of nesting habitat had been reduced by 50% from 0.8ha to 0.4ha. This led to overcrowding, increased conflict and displacement of some roseate terns.

Given the importance of the island to the regional tern population, discussions about restoration work had begun in the 1990s, but the cost and complex process of obtaining the necessary permits meant that work did not begin until 2016. The project was a partnership between MassWildlife, the US Army Corps of Engineers and the local town of Marion, Massachusetts.

The project would:

Bird Island is a small (c.0.8 hectare) island in Buzzards Bay, which supports important numbers of roseate and common terns. It has been intensively managed for terns since the late 1960s by the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife (MassWildlife).

The low island consists mainly of eroded glacial till protected by a riprap seawall originally built in the 1830s; it is exposed to wave action from the southwest and washed over in severe storms. The original revetment was built with a vertical face which had become damaged and the island eroded over the years. Low lying areas became salt marsh and were no longer suitable for tern nesting. By 2012 the amount of nesting habitat had been reduced by 50% from 0.8ha to 0.4ha. This led to overcrowding, increased conflict and displacement of some roseate terns.

Given the importance of the island to the regional tern population, discussions about restoration work had begun in the 1990s, but the cost and complex process of obtaining the necessary permits meant that work did not begin until 2016. The project was a partnership between MassWildlife, the US Army Corps of Engineers and the local town of Marion, Massachusetts.

The project would:

- rebuild the revetment to be wider, higher and sloping faced

- nourish the island with sand and gravel

- plant native vegetation

Beginning in 2016, the revetment was rebuilt, a ring of cobble was added around the island to provide adults terns with a less vegetated area for provisioning chicks, part of the island was raised by a foot to reduce overwash, and voids in the revetment were chinked with 15-20mm stones to prevent common terns becoming trapped (unlike roseate terns they could not climb out of gaps between the large stones of the revetment). In 2017 before the breeding season, the seawall was completed sand and gravel added to the interior and native plants planted.

Overall, the modifications functioned as desired, but there were some unexpected issues during the 2017 breeding season. The fill material added to the island included too much fine-grained material, impeding drainage and creating substantial puddling after rainfall. In addition, the low relief of the island meant water did not move laterally so that for much of the season a large part of the island’s surface remained damp with algae growing in some areas. This particularly affected roseate terns because the nest box clusters had by coincidence been placed in some of the worst areas and evaporation under the boxes was low. Wardens moved many unoccupied nest boxes from the saturated areas to encourage roseate terns to nest in safer areas. A second issue was the volume of fill. A design modification made after the first construction season involved raising the elevation of the northern half of the island by a foot to reduce overwash; however, there was a deficit of material and certain areas remained prone to puddling or tidal overwash. Before the 2018 breeding season MassWildlife and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers implemented measures to resolve drainage problems by construction and augmentation of rock-filled drainage channels and the addition of a 6” coarse gravel cap across the island, which appeared to be successful in eliminating the flooding issues.

Figure 14. Roseate tern numbers in Buzzards Bay; note the drop in numbers at Bird Island in 2017 and accompanying spike in numbers at Ram Island (MassWildlife)

Figure 14. Roseate tern numbers in Buzzards Bay; note the drop in numbers at Bird Island in 2017 and accompanying spike in numbers at Ram Island (MassWildlife)

The construction on Bird Island and subsequent flooding caused breeding roseate tern numbers to drop significantly (48%) in 2017 with birds apparently relocating to other islands in Buzzards Bay. In 2018 roseate tern numbers returned to pre-construction levels.

The overall cost of the project was in the region of US$6million, of which 65% was funded by the US federal government through the US Army Corps of Engineers Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration programme.

Lessons learned from the project include:

1) Staging construction between several breeding seasons was advantageous as issues identified in the first season could be addressed before project completion.

2) Specification of materials such as fill need careful scrutiny; but it is impossible to write a perfect specification or to control for unexpected interpretation

of an agreed specification.

3) Regular site visits and good communication with contractors are critical to progress and to heading off potential problems early.

Lessons learned from the project include:

1) Staging construction between several breeding seasons was advantageous as issues identified in the first season could be addressed before project completion.

2) Specification of materials such as fill need careful scrutiny; but it is impossible to write a perfect specification or to control for unexpected interpretation

of an agreed specification.

3) Regular site visits and good communication with contractors are critical to progress and to heading off potential problems early.

Figure 15. Map of little tern colonies (yellow dots) and Sandwich Tern colonies (brown dots) around the Irish Sea in 2019 (RSPB)

Figure 15. Map of little tern colonies (yellow dots) and Sandwich Tern colonies (brown dots) around the Irish Sea in 2019 (RSPB)

RSPB Hodbarrow, England: reforming and enlarging an island

Hodbarrow is on the coast of Cumbria, in North West England, one of many tern colonies on the edge of the Irish Sea. The site was originally an iron ore mine, which closed in 1968, and was acquired by the RSPB in the mid-1980s. As part of the mining operations a large area had been enclosed by a sea wall, after the mine closed this area was closed creating a freshwater lagoon. Even before the mine closed slag had been dumped within the sea wall, the top of this slag heap was left exposed as a large open area connected to the sea wall when the lagoon flooded. Early in the RSPB’s ownership a channel was dug in the slag to create a low-lying island for nesting birds (including terns); at this point several spits were also created.

Hodbarrow is on the coast of Cumbria, in North West England, one of many tern colonies on the edge of the Irish Sea. The site was originally an iron ore mine, which closed in 1968, and was acquired by the RSPB in the mid-1980s. As part of the mining operations a large area had been enclosed by a sea wall, after the mine closed this area was closed creating a freshwater lagoon. Even before the mine closed slag had been dumped within the sea wall, the top of this slag heap was left exposed as a large open area connected to the sea wall when the lagoon flooded. Early in the RSPB’s ownership a channel was dug in the slag to create a low-lying island for nesting birds (including terns); at this point several spits were also created.

Hodbarrow supported a breeding population of Sandwich and little terns once the mine closed. But in the early 2000s lesser black-backed gulls Larus fuscus displaced from the roof of nearby Haverigg Prison took up residence on the island and as numbers increased, little tern numbers fell sharply, deserting in 2008. In 2010 foxes, probably attracted by the large gull colony, caused the rest of the breeding seabirds to desert. They eventually returned to Hodbarrow following the introduction of an in-water fox fence.

The re-established colony is managed to limit vegetation growth by mechanical scraping at least once in every 5-year management plan cycle; supplemented by strimming and spraying in other years. The logistics and expense of getting a digger to the site means that the entire island is usually scraped to bare in the years when scraping takes place.

As the colony grew it was noted that areas of loose slag were dominated by black-headed gulls and Sandwich terns, with little terns on peripheral areas of hard packed slag. So, prior to 2019 breeding season, with the benefit of a SSSI improvement grant, approximately 1/3 ha of new habitat was added to the island, making it 10-20m wider. New areas were created with slag from the raised area of main slag heap, moved by digger to a dumper and then taken to the island across a temporary bridge of slag created for the purpose. This was deposited into the shallower areas of the lagoon adjacent to the island or spread once above water level. At the same time additional loose slag was added to depressions in the hard pack slag where the little tern’s nest to prevent flooding of those areas due to slow draining of the hard-packed material.

The total cost of the habitat creation was approximately £10,000 for hire of a digger and dumper to move the slag. SSSI consent was required, and all work done outside of the breeding season. Subject to funding, the Reserve team feel that up to an additional hectare of breeding habitat could still be added to the island before the remaining areas of the lagoon are too deep for the creation of any further new habitat to be viable.

Utopia, Texel, The Netherlands: lagoon islands for Sandwich terns

On this site behind the sea wall on the east side of the Wadden Sea island of Texel, 28 ha of former pasture fields has been converted by Natuurmonumenten, a Dutch conservation organisation, for avocets, spoonbills and tern species. The development started in 2010 and finished in the winter of 2011. Utopia is designed with 14 man-made islands at top water level which become connected as water levels fall. These cover a much higher proportion of the lagoon than would be found in an equivalent UK site, but there are no foxes on Texel, so there is less need to provide isolated islands.

The islands are very flat and low, about 10cm above top water level meaning rats can’t burrow into them. Half of the island area was capped with 5-10cm of shingle which is replenished regularly, and the rest was left as bare mud. The lagoon floor is terraced so that at spring top water level, the water is 10cm deep over one third of the lagoon, 20cm over the next third and 30cm deep over the remaining third, meaning that as water levels draw down, large expanses of wet mud are exposed. This detailed and static land forming is possible because there is no tidal influence. Salt water comes through the seawall through seepage, however there is also a pump and seawater can be pumped in if needed. Sandwich terns arrived approximately 3 years after it was built, believed to be relocating from other colonies on Texel. In 2015, there were a record-breaking 6000 nesting Sandwich terns, although the numbers do fluctuate annually. Little terns have been observed at Utopia, but although there have been up to 5 pairs recorded nesting, they have never successfully hatched a chick. The causes of these nest failures are unknown, although one theory is that the islands are too far from their food source.

On this site behind the sea wall on the east side of the Wadden Sea island of Texel, 28 ha of former pasture fields has been converted by Natuurmonumenten, a Dutch conservation organisation, for avocets, spoonbills and tern species. The development started in 2010 and finished in the winter of 2011. Utopia is designed with 14 man-made islands at top water level which become connected as water levels fall. These cover a much higher proportion of the lagoon than would be found in an equivalent UK site, but there are no foxes on Texel, so there is less need to provide isolated islands.

The islands are very flat and low, about 10cm above top water level meaning rats can’t burrow into them. Half of the island area was capped with 5-10cm of shingle which is replenished regularly, and the rest was left as bare mud. The lagoon floor is terraced so that at spring top water level, the water is 10cm deep over one third of the lagoon, 20cm over the next third and 30cm deep over the remaining third, meaning that as water levels draw down, large expanses of wet mud are exposed. This detailed and static land forming is possible because there is no tidal influence. Salt water comes through the seawall through seepage, however there is also a pump and seawater can be pumped in if needed. Sandwich terns arrived approximately 3 years after it was built, believed to be relocating from other colonies on Texel. In 2015, there were a record-breaking 6000 nesting Sandwich terns, although the numbers do fluctuate annually. Little terns have been observed at Utopia, but although there have been up to 5 pairs recorded nesting, they have never successfully hatched a chick. The causes of these nest failures are unknown, although one theory is that the islands are too far from their food source.

RSPB Wallasea Island, England: landscape scale habitat creation

Wallasea Island Wild Coast Project created 670 ha of new intertidal habitat on a low-lying coastal island using clean soil excavated during the Crossrail project in London. The site was previously farmland surrounded by seawalls which it had become uneconomically viable to maintain, so without these interventions the expected outcome would have been a seawall breach and flooding of flat land, with an impact on tidal flows in the adjoining estuary. The project design provided features including mudflats, salt marsh, saline lagoons and a range of island designs, incorporating ridges covered with shingle, sand and cockle shells for nesting terns and ringed plovers. Using waste material from Crossrail tunnels meant that the land could be raised, ensuring that the project was buffered against sea level rises due to climate change and allowing the creation of the specifically designed features by GPS-guided bulldozers with blade heights set according to 3D computer models. The cost of material transportation was covered by the Crossrail project, which would have otherwise had to find an alternative site for disposal of the excavated material. Wallasea exemplifies the complexity of such large-scale projects, taking 16 years from the initial identification of the potential of the site to the flooding of the first area in 2015. The initial stages of the project included the construction of a jetty and infrastructure to allow the transport and distribution of materials (Ausden et al. 2015).

As well as creating a broad range of intertidal habitats the Wallasea also provides a range of other benefits to society including flood defence, carbon sequestration, benefits to fisheries and human enjoyment and well-being. It has also proved immediately attractive to breeding common terns, with 8 pairs in 2016, 26 pairs in 2017, 43 pairs in 2018 and 56 pairs in 2019.

Wallasea Island Wild Coast Project created 670 ha of new intertidal habitat on a low-lying coastal island using clean soil excavated during the Crossrail project in London. The site was previously farmland surrounded by seawalls which it had become uneconomically viable to maintain, so without these interventions the expected outcome would have been a seawall breach and flooding of flat land, with an impact on tidal flows in the adjoining estuary. The project design provided features including mudflats, salt marsh, saline lagoons and a range of island designs, incorporating ridges covered with shingle, sand and cockle shells for nesting terns and ringed plovers. Using waste material from Crossrail tunnels meant that the land could be raised, ensuring that the project was buffered against sea level rises due to climate change and allowing the creation of the specifically designed features by GPS-guided bulldozers with blade heights set according to 3D computer models. The cost of material transportation was covered by the Crossrail project, which would have otherwise had to find an alternative site for disposal of the excavated material. Wallasea exemplifies the complexity of such large-scale projects, taking 16 years from the initial identification of the potential of the site to the flooding of the first area in 2015. The initial stages of the project included the construction of a jetty and infrastructure to allow the transport and distribution of materials (Ausden et al. 2015).

As well as creating a broad range of intertidal habitats the Wallasea also provides a range of other benefits to society including flood defence, carbon sequestration, benefits to fisheries and human enjoyment and well-being. It has also proved immediately attractive to breeding common terns, with 8 pairs in 2016, 26 pairs in 2017, 43 pairs in 2018 and 56 pairs in 2019.

Marker Wadden, The Netherlands: restoring natural shorelines

The Marker Wadden is large scale project to restore the Markermeer, one of the largest freshwater lakes in western Europe, by constructing islands, marshes and mud flats from the sediments that have accumulated in the lake in recent decades. The Markermeer lost most of its natural shores to land reclamation and flood protection measures and suffered from heavy siltation. As a result, fish and bird populations declined dramatically. The islands are being constructed from the excess silt within the lake and are designed to further trap silt and sediment helping to improve the turbidity of the lake. The islands are being designed with natural shorelines, providing both habitat for wildlife and areas for recreational purposes. The Marker Wadden is one of the biggest nature restoration projects in western Europe, aiming to restore an area of up to 100km2. Construction began in April 2016 and by the 2017 breeding season there were already significant numbers of breeding birds using the site, despite ongoing construction.

The Marker Wadden is large scale project to restore the Markermeer, one of the largest freshwater lakes in western Europe, by constructing islands, marshes and mud flats from the sediments that have accumulated in the lake in recent decades. The Markermeer lost most of its natural shores to land reclamation and flood protection measures and suffered from heavy siltation. As a result, fish and bird populations declined dramatically. The islands are being constructed from the excess silt within the lake and are designed to further trap silt and sediment helping to improve the turbidity of the lake. The islands are being designed with natural shorelines, providing both habitat for wildlife and areas for recreational purposes. The Marker Wadden is one of the biggest nature restoration projects in western Europe, aiming to restore an area of up to 100km2. Construction began in April 2016 and by the 2017 breeding season there were already significant numbers of breeding birds using the site, despite ongoing construction.

Sternenschiereiland, Zeebrugge, Belgium: creating a tern peninsula

The development of the port of Zeebrugge in the 1980s included creation of areas of sandy, sparsely vegetated and relatively undisturbed land in the western part of the harbour which attracted increasing numbers of plovers, terns and gulls. Habitat management in these areas was uneven, and they were scheduled for eventual development. Around 2000, a small artificial peninsula (2-3ha) was created along the eastern breakwater of the port of Zeebrugge. This was the first of a series of measures to compensate for the loss to development of nesting habitat in the western part of the harbour. During the next five years, the peninsula was further enlarged in four steps and during the breeding season in 2005 it reached about 10ha. The peninsula was intended to attract terns and was therefore named the “tern peninsula”, or Sternenschiereiland. The lower parts of the peninsula were covered with a 5cm layer of shell material to make them suitable for little terns. In order to minimise erosion and to support quick colonisation by black-headed gulls the elevated areas were planted with salt-resistant grasses. Most parts of the peninsula, however, were not planted because earlier experience in raised terrain showed that the area would become suitable for common terns within a few years anyway. The area requires ongoing vegetation maintenance and there is some mortality from the wind turbines which were already situated along the breakwater when Sternenschiereiland was created (Stienen et. al., 2005; Everaert and Stienen, 2007).

The development of the port of Zeebrugge in the 1980s included creation of areas of sandy, sparsely vegetated and relatively undisturbed land in the western part of the harbour which attracted increasing numbers of plovers, terns and gulls. Habitat management in these areas was uneven, and they were scheduled for eventual development. Around 2000, a small artificial peninsula (2-3ha) was created along the eastern breakwater of the port of Zeebrugge. This was the first of a series of measures to compensate for the loss to development of nesting habitat in the western part of the harbour. During the next five years, the peninsula was further enlarged in four steps and during the breeding season in 2005 it reached about 10ha. The peninsula was intended to attract terns and was therefore named the “tern peninsula”, or Sternenschiereiland. The lower parts of the peninsula were covered with a 5cm layer of shell material to make them suitable for little terns. In order to minimise erosion and to support quick colonisation by black-headed gulls the elevated areas were planted with salt-resistant grasses. Most parts of the peninsula, however, were not planted because earlier experience in raised terrain showed that the area would become suitable for common terns within a few years anyway. The area requires ongoing vegetation maintenance and there is some mortality from the wind turbines which were already situated along the breakwater when Sternenschiereiland was created (Stienen et. al., 2005; Everaert and Stienen, 2007).

Neeltje Jans, The Netherlands: recreating dunes

Neeltje Jans, an artificial island, approximately 285 hectares large, which was built to facilitate the construction of the Oosterscheldekering (Eastern Scheldt storm surge barrier). Neeltje Jans is one of the two artificial islands that make up the Oosterscheldekering, the building of which took over 10 years. Once the work was completed in 1986, the conservation bodies: Natuurmonumenten and Het Zeeuwse Landschap worked together to transform part of the island into a nature reserve. This consisted of removing the rubble and laying tons of sand relying on the wind to create natural dunes. Wind-blown and bird-carried seeds gradually vegetated the island. This transformation continued naturally with wildlife growing and arriving until it became a nature reserve ‘Nationaal Park Oosterschelde’. There are currently two little tern breeding areas on Neeltje Jans.

Little terns started nesting at the northern site approximately 7 years ago. The area is seaward facing with some shelter; however it does flood periodically with 3 metre high tides. The beach is asphalt which is covered with sand however due to erosion as a result of flooding and wind; sand replenishment is required. This covers a stretch of 50metres on the beach and adds 80cm height. Rijkswaterstaat is the organisation currently responsible for this and within the last 7 years they have done this twice. Volunteers add shells and stones to this area to further attract the little terns. The rest of Neeltje Jans targets tourism with an information centre and a theme park.

Neeltje Jans, an artificial island, approximately 285 hectares large, which was built to facilitate the construction of the Oosterscheldekering (Eastern Scheldt storm surge barrier). Neeltje Jans is one of the two artificial islands that make up the Oosterscheldekering, the building of which took over 10 years. Once the work was completed in 1986, the conservation bodies: Natuurmonumenten and Het Zeeuwse Landschap worked together to transform part of the island into a nature reserve. This consisted of removing the rubble and laying tons of sand relying on the wind to create natural dunes. Wind-blown and bird-carried seeds gradually vegetated the island. This transformation continued naturally with wildlife growing and arriving until it became a nature reserve ‘Nationaal Park Oosterschelde’. There are currently two little tern breeding areas on Neeltje Jans.

Little terns started nesting at the northern site approximately 7 years ago. The area is seaward facing with some shelter; however it does flood periodically with 3 metre high tides. The beach is asphalt which is covered with sand however due to erosion as a result of flooding and wind; sand replenishment is required. This covers a stretch of 50metres on the beach and adds 80cm height. Rijkswaterstaat is the organisation currently responsible for this and within the last 7 years they have done this twice. Volunteers add shells and stones to this area to further attract the little terns. The rest of Neeltje Jans targets tourism with an information centre and a theme park.

Relevant sections of Conservation Evidence

Action: Provide artificial nesting sites for ground and tree-nesting seabirds: https://www.conservationevidence.com/actions/480

Action: Remove vegetation to create nesting areas: https://www.conservationevidence.com/intervention/view/505

Action: Use decoys to attract birds to safe areas: https://www.conservationevidence.com/actions/586

Action: Provide artificial nesting sites for ground and tree-nesting seabirds: https://www.conservationevidence.com/actions/480

Action: Remove vegetation to create nesting areas: https://www.conservationevidence.com/intervention/view/505

Action: Use decoys to attract birds to safe areas: https://www.conservationevidence.com/actions/586

References

Ausden M, Dixon M, Lock L, Miles R, Richardson N & Scott C. (2018) SEA Change in the Beneficial Use of Dredged Sediment. Technical Report. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

Ausden, M., Dixon, M., Fancy, R., Hirons, G., Kew, J., Mcloughlin, P., Scott, C., Sharpe, J. and Tyas, C. (2015) Wallasea: a wetland designed for the future. British Wildlife. August 2015: 382–383.

Everaert, J. & Stienen, E.W.M. (2007) Impact of wind turbines on birds in Zeebrugge (Belgium): Significant effect on breeding tern colony due to collisions. Biodiversity Conservation 16: 3345-3359.

Parsons, M., Lawson, J., Lewis, M., Lawrence, R. & Kuepfer, A. (2015) Quantifying foraging areas of little tern around its breeding colony SPA during chick-rearing. JNCC Report No. 548. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough.

Schippers, P., Snep, R.P.H., Schotman, A.G.M., Jochem R., Stienen E.W.M. and Slim P.A. (2009) Seabird metapopulations: searching for alternative breeding habitats. Population Ecology 51: 459-470.

Stienen E.W.M., Courtens W., Van de Walle M., Van Waeyenberge J., and Kuijken E. (2005) Harbouring nature: port development and dynamic birds provide clues for conservation. In: Herrier J.-L., J. Mees, A. Salman, J. Seys, H. Van Nieuwenhuyse and I. Dobbelaere (Eds). 2005. p381-392. Proceedings ‘Dunes and Estuaries 2005’ – International Conference on Nature Restoration Practices in European Coastal Habitats, Koksijde, Belgium, 19-23 September 2005 VLIZ Special Publication 19, xiv + 685 pp

Wilson L. J., Black J., Brewer, M. J., Potts, J. M., Kuepfer, A., Win I., Kober K., Bingham C., Mavor R. and Webb A. (2014). Quantifying usage of the marine environment by terns Sterna sp. around their breeding colony SPAs. JNCC Report No. 500. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Carolyn Mostello (MassWildlife), Dave Blackledge (RSPB Cumbria Coast), Ivan Lang (RSPB Pagham Harbour), Wez Smith (RSPB Langstone and Chichester Harbours), and Leigh Lock (RSPB).

Ausden M, Dixon M, Lock L, Miles R, Richardson N & Scott C. (2018) SEA Change in the Beneficial Use of Dredged Sediment. Technical Report. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

Ausden, M., Dixon, M., Fancy, R., Hirons, G., Kew, J., Mcloughlin, P., Scott, C., Sharpe, J. and Tyas, C. (2015) Wallasea: a wetland designed for the future. British Wildlife. August 2015: 382–383.

Everaert, J. & Stienen, E.W.M. (2007) Impact of wind turbines on birds in Zeebrugge (Belgium): Significant effect on breeding tern colony due to collisions. Biodiversity Conservation 16: 3345-3359.

Parsons, M., Lawson, J., Lewis, M., Lawrence, R. & Kuepfer, A. (2015) Quantifying foraging areas of little tern around its breeding colony SPA during chick-rearing. JNCC Report No. 548. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough.

Schippers, P., Snep, R.P.H., Schotman, A.G.M., Jochem R., Stienen E.W.M. and Slim P.A. (2009) Seabird metapopulations: searching for alternative breeding habitats. Population Ecology 51: 459-470.

Stienen E.W.M., Courtens W., Van de Walle M., Van Waeyenberge J., and Kuijken E. (2005) Harbouring nature: port development and dynamic birds provide clues for conservation. In: Herrier J.-L., J. Mees, A. Salman, J. Seys, H. Van Nieuwenhuyse and I. Dobbelaere (Eds). 2005. p381-392. Proceedings ‘Dunes and Estuaries 2005’ – International Conference on Nature Restoration Practices in European Coastal Habitats, Koksijde, Belgium, 19-23 September 2005 VLIZ Special Publication 19, xiv + 685 pp

Wilson L. J., Black J., Brewer, M. J., Potts, J. M., Kuepfer, A., Win I., Kober K., Bingham C., Mavor R. and Webb A. (2014). Quantifying usage of the marine environment by terns Sterna sp. around their breeding colony SPAs. JNCC Report No. 500. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Carolyn Mostello (MassWildlife), Dave Blackledge (RSPB Cumbria Coast), Ivan Lang (RSPB Pagham Harbour), Wez Smith (RSPB Langstone and Chichester Harbours), and Leigh Lock (RSPB).

Appendix 1. Habitat Creation Checklist

This is a starting point providing issues to consider when contemplating a habitat creation or restoration project; it was written with UK based projects in mind, but the general principles will apply more widely.

Target species behaviour and natural history

Species presence, breeding data and trends (site and region)

Offshore and localised food supply (any studies or information sources)

Appropriate terrestrial habitat and substrate

Access to alternative resources e.g. fresh or brackish water

Vegetation characteristics

Predator presence (evidence, including absence of species which might be vulnerable)

Potential for interspecific competition (gull species, Oystercatchers etc)

Proximity to other colonies and position relative to the wider colony network (including migration routes)

Coastal processes, coastal morphology, tides and erosion

Natural coastal changes (accreting or eroding) – historic photos may help

Tides and tidal flooding

Offshore processes (accretion, erosion, sediment cells)

Bathymetric data (can show beach change)

Land drainage etc affecting site water levels

Climate change including sea level rise

Local sea level rise and impact of storm surges

Sustainability of food supply

Opportunities linked to climate change e.g. habitat mitigation

Stakeholders, landowners and community interests

Managed realignment plans e.g. Environment Agency

Shoreline Management Plans (SMPs) and Action Plans

Natural England Site Improvement Plans (SIPs)

Community economics (e.g. tourism, commercial fishing, navigation)

Community interests (e.g. boating, recreation)

Landowner permissions

Legal considerations (permissions and licences)

European habitats directive (SAC and SPA)

National designations e.g. SSSI/ASSI consents

Use of dredgings

Marine and navigation

Crown Estates

Disturbance Licence (statutory agency)

Existing management plans

Colony management

Ability and resources available to manage the colony into the future

Fencing (anti-predator/anti-disturbance)

Vegetation management

Nesting substrate (nesting area)

Decoys and lures (for new nesting areas)

Lagoon/sheltered area, freshwater (serving as an all-weather source of small fish).

Signage and interpretation

Wardening

Other

Pollution risk

Development plans, onshore and offshore

This is a starting point providing issues to consider when contemplating a habitat creation or restoration project; it was written with UK based projects in mind, but the general principles will apply more widely.

Target species behaviour and natural history

Species presence, breeding data and trends (site and region)

Offshore and localised food supply (any studies or information sources)

Appropriate terrestrial habitat and substrate

Access to alternative resources e.g. fresh or brackish water

Vegetation characteristics

Predator presence (evidence, including absence of species which might be vulnerable)

Potential for interspecific competition (gull species, Oystercatchers etc)

Proximity to other colonies and position relative to the wider colony network (including migration routes)

Coastal processes, coastal morphology, tides and erosion

Natural coastal changes (accreting or eroding) – historic photos may help

Tides and tidal flooding

Offshore processes (accretion, erosion, sediment cells)

Bathymetric data (can show beach change)

Land drainage etc affecting site water levels

Climate change including sea level rise

Local sea level rise and impact of storm surges

Sustainability of food supply

Opportunities linked to climate change e.g. habitat mitigation

Stakeholders, landowners and community interests

Managed realignment plans e.g. Environment Agency

Shoreline Management Plans (SMPs) and Action Plans

Natural England Site Improvement Plans (SIPs)

Community economics (e.g. tourism, commercial fishing, navigation)

Community interests (e.g. boating, recreation)

Landowner permissions

Legal considerations (permissions and licences)

European habitats directive (SAC and SPA)

National designations e.g. SSSI/ASSI consents

Use of dredgings

Marine and navigation

Crown Estates

Disturbance Licence (statutory agency)

Existing management plans

Colony management

Ability and resources available to manage the colony into the future

Fencing (anti-predator/anti-disturbance)

Vegetation management

Nesting substrate (nesting area)

Decoys and lures (for new nesting areas)

Lagoon/sheltered area, freshwater (serving as an all-weather source of small fish).

Signage and interpretation

Wardening

Other

Pollution risk

Development plans, onshore and offshore