Citation: Babcock and Booth (2020) Diversionary Feeding Kestrels. Tern Conservation Best Practice. Produced for “Improving the conservation prospects of the priority species roseate tern throughout its range in the UK and Ireland” LIFE14 NAT/UK/000394’

Last updated: October 2020

This is a live document we update regularly. If you have comments and suggestions, please email Chantal.Macleod-Nolan@rspb.org.uk

Last updated: October 2020

This is a live document we update regularly. If you have comments and suggestions, please email Chantal.Macleod-Nolan@rspb.org.uk

| Babcock and Booth (2020) Diversionary Feeding Kestrels. Tern Conservation Best Practice. | |

| File Size: | 1939 kb |

| File Type: | |

Key Messages

- Diversionary feeding kestrels can significantly reduce predation on little tern chicks at little tern colonies but has rarely been attempted for other avian predators or other tern species.

- To be most effective diversionary feeding should take place close to kestrel nests; although access to these is not always possible. Diversionary feeding at the tern colony has been attempted in several places with variable levels of success.

- Predation pressure on little terns is closely linked to the availability of small mammals in the local area.

- Diversionary feeding requires a substantial investment of time and effort.

Information

Diversionary feeding is the use of food to divert the activity or behaviour of a species from an action that causes a negative impact, without the intention of increasing the density of the target population (Kubasiewicz et. al. 2015). It is not the same as supplementary feeding, which is a conservation method to improve the population viability or density of the target species or population.

In the case of terns, diversionary feeding has most frequently been attempted to divert Eurasian kestrel Falco tinnunculus from predating little tern Sternula albifrons chicks. Little terns are one of the UK’s rarest breeding seabirds and population declines have been attributed reductions in breeding success (Pickerell 2004) therefore conservation efforts have often focussed on improving productivity and have justified intensive management methods. Most little tern colonies are fenced, have signage and many have warden protection.

The most regularly reported predators at little tern colonies are foxes and kestrels (Ratcliffe, 2003). While fencing and wardening can reduce mammal predation, and human disturbance, they are less efficient in deterring avian predators.

Diversionary feeding of kestrels can boost tern productivity, however not all kestrel pairs will readily take alternative food, and it is not necessary in years when there is abundant small mammal prey. A diversionary feeding programme requires a substantial investment of staff and volunteer time and effort: locating kestrel nests and providing feeding platforms, provisioning those platforms and monitoring both predation at the colony and the prey items fed to chicks in order to understand whether the intervention is effective.

Diversionary feeding may also artificially boost local kestrel populations and thereby prolonging or increasing their predation impact on little tern colonies something which must be considered before setting up a diversionary feeding programme. Colony managers should also have a clear idea of objectives and how results will be measured. It would be helpful to report on the method, effort, results, and costs to add to the existing body of knowledge about diversionary feeding.

Diversionary feeding is the use of food to divert the activity or behaviour of a species from an action that causes a negative impact, without the intention of increasing the density of the target population (Kubasiewicz et. al. 2015). It is not the same as supplementary feeding, which is a conservation method to improve the population viability or density of the target species or population.

In the case of terns, diversionary feeding has most frequently been attempted to divert Eurasian kestrel Falco tinnunculus from predating little tern Sternula albifrons chicks. Little terns are one of the UK’s rarest breeding seabirds and population declines have been attributed reductions in breeding success (Pickerell 2004) therefore conservation efforts have often focussed on improving productivity and have justified intensive management methods. Most little tern colonies are fenced, have signage and many have warden protection.

The most regularly reported predators at little tern colonies are foxes and kestrels (Ratcliffe, 2003). While fencing and wardening can reduce mammal predation, and human disturbance, they are less efficient in deterring avian predators.

Diversionary feeding of kestrels can boost tern productivity, however not all kestrel pairs will readily take alternative food, and it is not necessary in years when there is abundant small mammal prey. A diversionary feeding programme requires a substantial investment of staff and volunteer time and effort: locating kestrel nests and providing feeding platforms, provisioning those platforms and monitoring both predation at the colony and the prey items fed to chicks in order to understand whether the intervention is effective.

Diversionary feeding may also artificially boost local kestrel populations and thereby prolonging or increasing their predation impact on little tern colonies something which must be considered before setting up a diversionary feeding programme. Colony managers should also have a clear idea of objectives and how results will be measured. It would be helpful to report on the method, effort, results, and costs to add to the existing body of knowledge about diversionary feeding.

Published Research

Kubasiewicz et. al. (2015) reviewed the literature on diversionary feeding (across many taxa) and evaluated factors contributing to its success or failure. The level of success varied greatly, and even successful uptake of diversionary food did not consistently produce the desired outcome. The study also found that although diversionary feeding is considered expensive, cost-benefit analyses were rarely conducted.

Smart & Amar (2018) compared annual kestrel predation and little tern success rates in six years with diversionary feeding and five years without. This analysis was coupled with an experimental approach at the Great Yarmouth colony where between 2005 and 2009 diversionary feeding was experimentally switched on and off in alternate years. Daily rates of kestrel predation at the colony and prey delivery rates at kestrel nests were compared between two years with diversionary feeding (2006 & 2008) and three years without (2005, 2007 & 2009). It was intended to balance the study with a third year of diversionary feeding, but the colony abandoned in 2010.

Annual estimates of little tern productivity were around twice as high in years with diversionary feeding. With an average little tern colony size of 246 pairs diversionary feeding resulted in an average of 216 (190-243) little tern chicks fledging compared with 103 (91-116) in years without feeding.

Three kestrel nests were monitored (one for three years and two for two years). When diversionary feeding took place 61-73% of food items brought to chicks were the diversionary food. When there was no diversionary feeding, 3.4 times more wild food items were brought to chicks including 6.2 times more little tern chicks than in years when feeding took place. This indicates that diversionary feeding successfully reduces the motivation to hunt.

Little tern chicks do not appear to be a favoured food, as when other wild prey items are provided the number of little tern chicks brought to the nest is reduced. However, a discrepancy between the number of little tern chicks predated and the number provided at kestrel nests suggests that adult birds often consume them, which is consistent with observations made by the authors. The pattern of predation and provisioning suggests that kestrels simply exploit food resources in relation to their availability and profitability at different times. This means diversionary feeding which is available and profitable to the kestrels can be an effective tool in reducing predation on little tern colonies.

Annual, seasonal and individual variation in the success of diversionary feeding may well be determined by individual kestrel behaviour, the timing of kestrel chick hatching relative to little tern chick hatching, the quality of foraging areas around kestrel nests and the availability of mammal prey.

Guidance for diversionary feeding resulting from this work:

Kubasiewicz et. al. (2015) reviewed the literature on diversionary feeding (across many taxa) and evaluated factors contributing to its success or failure. The level of success varied greatly, and even successful uptake of diversionary food did not consistently produce the desired outcome. The study also found that although diversionary feeding is considered expensive, cost-benefit analyses were rarely conducted.

Smart & Amar (2018) compared annual kestrel predation and little tern success rates in six years with diversionary feeding and five years without. This analysis was coupled with an experimental approach at the Great Yarmouth colony where between 2005 and 2009 diversionary feeding was experimentally switched on and off in alternate years. Daily rates of kestrel predation at the colony and prey delivery rates at kestrel nests were compared between two years with diversionary feeding (2006 & 2008) and three years without (2005, 2007 & 2009). It was intended to balance the study with a third year of diversionary feeding, but the colony abandoned in 2010.

Annual estimates of little tern productivity were around twice as high in years with diversionary feeding. With an average little tern colony size of 246 pairs diversionary feeding resulted in an average of 216 (190-243) little tern chicks fledging compared with 103 (91-116) in years without feeding.

Three kestrel nests were monitored (one for three years and two for two years). When diversionary feeding took place 61-73% of food items brought to chicks were the diversionary food. When there was no diversionary feeding, 3.4 times more wild food items were brought to chicks including 6.2 times more little tern chicks than in years when feeding took place. This indicates that diversionary feeding successfully reduces the motivation to hunt.

Little tern chicks do not appear to be a favoured food, as when other wild prey items are provided the number of little tern chicks brought to the nest is reduced. However, a discrepancy between the number of little tern chicks predated and the number provided at kestrel nests suggests that adult birds often consume them, which is consistent with observations made by the authors. The pattern of predation and provisioning suggests that kestrels simply exploit food resources in relation to their availability and profitability at different times. This means diversionary feeding which is available and profitable to the kestrels can be an effective tool in reducing predation on little tern colonies.

Annual, seasonal and individual variation in the success of diversionary feeding may well be determined by individual kestrel behaviour, the timing of kestrel chick hatching relative to little tern chick hatching, the quality of foraging areas around kestrel nests and the availability of mammal prey.

Guidance for diversionary feeding resulting from this work:

- Be consistent in the timing and frequency of feeding: e.g. twice daily at 0800 & 1600.

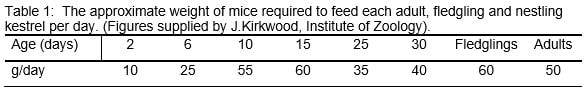

- Aim to provide a minimum of 100% of the daily food requirements of the kestrel family, making adjustments for number and age of the kestrel chicks and adults (see Table 1). It is just as important to avoid over feeding as under feeding so ensure that there is no build-up of old food in the feeding location.

- Purchase frozen food from a reputable company (e.g. Frozen Direct in the UK) and provide 50% mice and 50% day-old poultry chicks (if possible, poultry chicks are less expensive but will not meet all nutritional needs). Food should be defrosted in advance of feeding.

- Food should be provided as close to the kestrel nest as possible (around 2-5 m). This means the food is obvious to the kestrels and is unlikely to be taken by other species (e.g. corvids) as the kestrels will defend their nest. It may be necessary to erect a feeding platform and to construct a feeding pole to get food to near the nest and avoid scavenging by mammals.

- Feeding should begin as soon as kestrel chicks hatch. It may need to begin earlier with kestrel pairs that are new to diversionary feeding as there can be a delay in them learning to take the food.

- Feeding should end when the last kestrel chick has fledged.

- Spend time observing the kestrels and their response to the food until confident they are taking the diversionary food.

- Keep daily records of feeding activities and observations.

- Ensure you have kestrel on your disturbance license (in the UK) and any that any other legal/permitting requirements have been complied with).

Case Studies

Chesil Beach, England: diversionary feeding

At the Chesil little tern colony, which is managed by seasonal RSPB Wardens, in years of low kestrel predation the colony has achieved breeding productivity of up to c. 1.9 chicks per pair. In years when the level of kestrel predation was high productivity has fallen to c. 0.37 chicks per pair (Richard Archer, RSPB, pers com.) However, even when kestrels are active, with good diversionary feeding in place the colony has produced c. 0.7 chicks per pair.

This experience at this site suggests that several elements must be in place for effective diversionary feeding:

Chesil Beach, England: diversionary feeding

At the Chesil little tern colony, which is managed by seasonal RSPB Wardens, in years of low kestrel predation the colony has achieved breeding productivity of up to c. 1.9 chicks per pair. In years when the level of kestrel predation was high productivity has fallen to c. 0.37 chicks per pair (Richard Archer, RSPB, pers com.) However, even when kestrels are active, with good diversionary feeding in place the colony has produced c. 0.7 chicks per pair.

This experience at this site suggests that several elements must be in place for effective diversionary feeding:

- Early identification of kestrel nesting sites within c. 5 km of little tern colony; at Chesil one kestrel pair, which usually nests on nearby cliffs at Portland, is responsible for most little tern chick predation.

- Location of feeding stations close to kestrel nesting sites (in 2019, this was not possible with Portland pair, which had moved their nest site to a less accessible location).

- Effective location of secondary feeding stations near the little tern colony on kestrel flight lines. There is debate about whether secondary feeding stations close to the colony attract kestrels to the colony or whether they reduce tern chick predation. More data is needed.

- Good feeding station design to restrict access to food by non-target species, notably gulls and crows (for an example see the design used at Gronant).

- Adequate staffing and volunteers to maintain daily monitoring of feeding stations, restocking and removal of rotting material.

- Adequate health and safety preparation for staff and volunteers including a cool bag to store the kestrel food items (domestic chicks), hand sanitisers and gloves. These are not only essential for health and safety but also encourage more volunteers to participate in what is otherwise an unpleasant task.

- Communication with local people to reduce the risk of vandalism at feeding stations and to prevent the spread of misinformation about the purpose of diversionary feeding, e.g. that the feeders are there to poison kestrels (!).

- It is good conservation practise to ensure that a wild animal does not become dependent on artificial feeding and therefore feed it for the shortest time possible.

Gronant, Wales: diversionary feeding not required when other wild prey is abundant

Gronant dunes are part of an extensive network of dunes at the entrance to the Dee Estuary in North Wales, UK. The importance of the dune system as a whole is recognized by many conservation designations including Site of Special Scientific Interest, Ramsar site, Special Protection Area and Special Area of Conservation. They also include the only colony of breeding little terns in North Wales.

In 2017, with a grant from Wales Ornithological Society, the North Wales Little Tern Group, the community project that supports Denbighshire County Council’s wardening at Gronant dunes, started a diversionary feeding project to reduce the impact of predation on tern chicks by kestrels. A diversionary feeding station was deployed at the colony, but no food was taken by any species and kestrel predation of tern chicks was negligible. It is thought that an abundance of small mammals in this area in 2017 provided the kestrels with everything they needed.

Gronant dunes are part of an extensive network of dunes at the entrance to the Dee Estuary in North Wales, UK. The importance of the dune system as a whole is recognized by many conservation designations including Site of Special Scientific Interest, Ramsar site, Special Protection Area and Special Area of Conservation. They also include the only colony of breeding little terns in North Wales.

In 2017, with a grant from Wales Ornithological Society, the North Wales Little Tern Group, the community project that supports Denbighshire County Council’s wardening at Gronant dunes, started a diversionary feeding project to reduce the impact of predation on tern chicks by kestrels. A diversionary feeding station was deployed at the colony, but no food was taken by any species and kestrel predation of tern chicks was negligible. It is thought that an abundance of small mammals in this area in 2017 provided the kestrels with everything they needed.

In 2018, the diversionary feeding station was deployed again as kestrel presence increased and predation attempts in the little tern colony became more frequent. Mice were used at first and it took a while before they were taken by kestrels. Small poultry chicks were then provided, which the kestrels soon started to take. Up to three chicks were placed on the feeding station at a time and stocks were replenished most mornings. A trail camera was used to monitor use of the feeding station and from 2nd July showing kestrels taking chicks fairly consistently (Figure 1). Less predation of little terns was witnessed and there was a reduction in the presence of kestrels at the colony. Unfortunately, the data collected was insufficient for statistical analysis.

In 2019, the Gronant diversionary feeding station was deployed once consecutive aerial predation attempts had been observed indicating that kestrels were active in the area (and to avoid attracting them to the colony before this was the case). Diversionary feeding began on 17th June and continued until 17th July using only poultry chicks. The diversionary feeder was used much less than in 2018, however only low levels of predation were observed in the little tern colony, so it may be that other wild food was abundant in the area in 2019.

It should also be noted that other methods of deterring predation at the colony were also employed, including firing a starter pistol and warden presence.

Figure 2. The diversionary feeding station set up in a churchyard near Blakeney Point, and a kestrel using a feeding station (both photos, National Trust)

Figure 2. The diversionary feeding station set up in a churchyard near Blakeney Point, and a kestrel using a feeding station (both photos, National Trust)

Blakeney Point, England: the challenge of inaccessible kestrel nests in various directions

Blakeney Point on the Norfolk coast is an important site for breeding Sandwich and little terns and has a small colony of common terns. A 6.4 km spit of shingle and sand dunes, it also includes salt marshes, tidal mudflats and reclaimed farmland. Blakeney Point has been managed by the National Trust (UK) since 1912 and lies within the North Norfolk Coast Site of Special Scientific Interest and is also a Special Protection Area (SPA) and Ramsar site.

Diversionary feeding was started during the 2018 breeding season in response to heavy predation pressure from kestrels nesting in nearby villages including Cley, Blakeney, Morston and Stiffkey. As kestrel predation was already occurring at the tern colony a feeding station was established at the colony consisting of an open table on a tall pole (approximately 7 feet above the ground) with a trail camera so that visits to the table could be monitored. The prey items offered were poultry chicks. However, the kestrels approached the colony from the direction of their respective villages and didn’t show any interest in the table unless it was on their flight line.

Blakeney Point on the Norfolk coast is an important site for breeding Sandwich and little terns and has a small colony of common terns. A 6.4 km spit of shingle and sand dunes, it also includes salt marshes, tidal mudflats and reclaimed farmland. Blakeney Point has been managed by the National Trust (UK) since 1912 and lies within the North Norfolk Coast Site of Special Scientific Interest and is also a Special Protection Area (SPA) and Ramsar site.

Diversionary feeding was started during the 2018 breeding season in response to heavy predation pressure from kestrels nesting in nearby villages including Cley, Blakeney, Morston and Stiffkey. As kestrel predation was already occurring at the tern colony a feeding station was established at the colony consisting of an open table on a tall pole (approximately 7 feet above the ground) with a trail camera so that visits to the table could be monitored. The prey items offered were poultry chicks. However, the kestrels approached the colony from the direction of their respective villages and didn’t show any interest in the table unless it was on their flight line.

Figure 2. The diversionary feeding station set up in a churchyard near Blakeney Point, and a kestrel using a feeding station (both photos, National Trust)

Figure 2. The diversionary feeding station set up in a churchyard near Blakeney Point, and a kestrel using a feeding station (both photos, National Trust)

In 2019 diversionary feeding started earlier. A kestrel nest was located in a churchyard and a feeding station established close by which was used by the kestrels, as shown by trail camera footage (Figure 2). Other nests were on private land and access for diversionary feeding near the nest was not possible, so a secondary feeding station was again established at the colony. Again, it was not effective when it was not on a direct flight line. Feeding started before tern chicks had hatched and stopped when they fledged requiring a significant investment of staff time.

Communications with local communities was also important in this case. Unlike Chesil, where local concern was that diversionary feeding was a prelude to poisoning kestrels, some local people near Blakeney advocated lethal control of kestrels and had to be discouraged from pursuing this.

Blakeney Point illustrates the challenge of implementing diversionary feeding when there are multiple pairs of kestrels and the nests are not accessible. With the help of nest-finding volunteers it may be possible to improve the Blakeney diversionary feeding programme.

It may be useful to note that while diversionary feeding at a colony is often regarded as increasing the risk of drawing kestrels in, the Blakeney experience suggests that kestrels will ignore a feeding station which is not on their flight line, and so it seems unlikely that feeding stations act as an attractant for kestrels (although the potential for attracting corvids or other raptors may remain a concern).

Communications with local communities was also important in this case. Unlike Chesil, where local concern was that diversionary feeding was a prelude to poisoning kestrels, some local people near Blakeney advocated lethal control of kestrels and had to be discouraged from pursuing this.

Blakeney Point illustrates the challenge of implementing diversionary feeding when there are multiple pairs of kestrels and the nests are not accessible. With the help of nest-finding volunteers it may be possible to improve the Blakeney diversionary feeding programme.

It may be useful to note that while diversionary feeding at a colony is often regarded as increasing the risk of drawing kestrels in, the Blakeney experience suggests that kestrels will ignore a feeding station which is not on their flight line, and so it seems unlikely that feeding stations act as an attractant for kestrels (although the potential for attracting corvids or other raptors may remain a concern).

References

Kubasiewicz, L. M., Bunnefeld, N., Tulloch, A. I. T., Quine, C. P. and Park, K. J. (2015) Diversionary feeding: an effective management strategy for conservation conflict? Biodiversity and Conservation 25 (1) 1-22.

Ratcliffe, N (2003) Little terns in Britain and Ireland: Estimation and diagnosis of population trends. In R.I. Allcorn (Ed.) Proceedings of a symposium on Little Terns Sterna albifrons (pp.4–18). RSPB Research Report 8.

Smart, J. & Amar, A. (2018) Diversionary feeding as a means of reducing raptor predation at seabird breeding colonies. Journal for Nature Conservation, 46, 48‐55.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jen Smart (RSPB), Richard Archer (RSPB), Leighton Newman and Carl Booker (National Trust Blakeney Point), Chantal Macleod-Nolan (RSPB) and Henry Cook (North Wales Wildlife Trust).

Kubasiewicz, L. M., Bunnefeld, N., Tulloch, A. I. T., Quine, C. P. and Park, K. J. (2015) Diversionary feeding: an effective management strategy for conservation conflict? Biodiversity and Conservation 25 (1) 1-22.

Ratcliffe, N (2003) Little terns in Britain and Ireland: Estimation and diagnosis of population trends. In R.I. Allcorn (Ed.) Proceedings of a symposium on Little Terns Sterna albifrons (pp.4–18). RSPB Research Report 8.

Smart, J. & Amar, A. (2018) Diversionary feeding as a means of reducing raptor predation at seabird breeding colonies. Journal for Nature Conservation, 46, 48‐55.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jen Smart (RSPB), Richard Archer (RSPB), Leighton Newman and Carl Booker (National Trust Blakeney Point), Chantal Macleod-Nolan (RSPB) and Henry Cook (North Wales Wildlife Trust).