Citation: Babcock and Booth (2020) Chick Shelters. Tern Conservation Best Practice. Produced for “Improving the conservation prospects of the priority species roseate tern throughout its range in the UK and Ireland” LIFE14 NAT/UK/000394’

Last updated: October 2020

This is a live document we update regularly. If you have comments and suggestions, please email Chantal.Macleod-Nolan@rspb.org.uk

Last updated: October 2020

This is a live document we update regularly. If you have comments and suggestions, please email Chantal.Macleod-Nolan@rspb.org.uk

| Babcock and Booth (2020) Chick Shelters. Tern Conservation Best Practice. | |

| File Size: | 2478 kb |

| File Type: | |

Key Messages

- Chick shelters may be a useful tool for tern colony managers where birds nest in open areas which lack access to natural cover, providing some protection against weather and predators.

- The published evidence for the efficacy of shelters is mixed, especially for Sternula terns, but they may be useful as part of a suite of management interventions.

- There are various designs in use. Shelters with multiple entrances/exits will give chicks the best chance of avoiding predators. If a site is windy, shelters should be weighted down.

Information

Chick shelters are often used in tern colonies to provide protection from predators and extreme weather, especially if nesting areas lack vegetation or other features that would provide natural shelter, or where access to such features may be limited by other management interventions such as anti-predator fencing. Roseate tern Sterna dougallii chicks will often shelter in nest boxes if provided.

The disruptive patterning of young tern chicks and their instinct to freeze in response to danger show that camouflage is their primary defence against predators. However, there are many recorded cases of predation having a significant impact on tern colonies, so providing additional protection is a reasonable precaution. Shelters will be more effective against visual (e.g. avian) predators than those using scent, however, it is important to remember that some predators learn quickly and may begin to recognise chick shelters as a potential source of food. Monitoring should be in place to identify whether this is happening and if so the use of chick shelters should be immediately reviewed. A chick shelter design with four entrances was developed at RSPB Langstone Harbour following observations of predators waiting outside simple double-entrance shelters. Having a range of shelter designs, or changing shelter designs each season may make it more difficult for some predators to learn to identify them.

Young chicks cannot thermoregulate and are vulnerable to chilling during cold or wet weather or overheating in hot weather. Well-designed chick shelters can provide some protection against weather. However, at sites where windblown sand is a regular occurrence, monitoring of shelters will be necessary as chicks using shelters may be trapped if sand piles up around and in the shelter.

Deploying chick shelters at a known or prospective breeding site is an attempt to affect the behaviour of a wild bird, so the impact of using the shelters must be considered and any necessary permissions obtained. In the UK:

On a publicly-accessible site it is worth considering how the chick shelters will be perceived by visitors. It is important to avoid inadvertently attracting people into the nesting area either through curiosity about these strange objects, or because they are undertaking a beach clean and perceive them as litter. Signage and/or wardening may be helpful in explaining where the no-go areas are and what chick shelters they look like, so well-meaning people don’t remove or collect them.

Chick shelters are often used in tern colonies to provide protection from predators and extreme weather, especially if nesting areas lack vegetation or other features that would provide natural shelter, or where access to such features may be limited by other management interventions such as anti-predator fencing. Roseate tern Sterna dougallii chicks will often shelter in nest boxes if provided.

The disruptive patterning of young tern chicks and their instinct to freeze in response to danger show that camouflage is their primary defence against predators. However, there are many recorded cases of predation having a significant impact on tern colonies, so providing additional protection is a reasonable precaution. Shelters will be more effective against visual (e.g. avian) predators than those using scent, however, it is important to remember that some predators learn quickly and may begin to recognise chick shelters as a potential source of food. Monitoring should be in place to identify whether this is happening and if so the use of chick shelters should be immediately reviewed. A chick shelter design with four entrances was developed at RSPB Langstone Harbour following observations of predators waiting outside simple double-entrance shelters. Having a range of shelter designs, or changing shelter designs each season may make it more difficult for some predators to learn to identify them.

Young chicks cannot thermoregulate and are vulnerable to chilling during cold or wet weather or overheating in hot weather. Well-designed chick shelters can provide some protection against weather. However, at sites where windblown sand is a regular occurrence, monitoring of shelters will be necessary as chicks using shelters may be trapped if sand piles up around and in the shelter.

Deploying chick shelters at a known or prospective breeding site is an attempt to affect the behaviour of a wild bird, so the impact of using the shelters must be considered and any necessary permissions obtained. In the UK:

- If the site is a Site/Area of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI or ASSI) permission needs to be sought from the relevant statutory agency.

- Consent from the landowner will be required, this could be as part of an agreed Management Plan.

- Roseate terns and little tern Sternula albifrons are on Schedule 1 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981) so a disturbance licence is required for any activity around breeding birds of these species. Using chick shelters at a site that does not have roseate or little terns present, or before they arrive does not require a disturbance licence.

On a publicly-accessible site it is worth considering how the chick shelters will be perceived by visitors. It is important to avoid inadvertently attracting people into the nesting area either through curiosity about these strange objects, or because they are undertaking a beach clean and perceive them as litter. Signage and/or wardening may be helpful in explaining where the no-go areas are and what chick shelters they look like, so well-meaning people don’t remove or collect them.

Figure 1. A chick shelter designed to deter raptor predation (from Jenks-Jay, 1982)

Figure 1. A chick shelter designed to deter raptor predation (from Jenks-Jay, 1982)

Published Research

A study by Jenks-Jay (1982) found that at seven least tern Sternula antillarum colonies on Nantucket Island, Massachusetts, USA, predation of chicks by raptors (American kestrel Falco sparverius and Northern harrier Circus hudsonius) was greatly reduced following the provision of chick shelters. The shelters were 43 cm high cones made from 11 repurposed snow fence slats with a 66 cm basal diameter placed around a stake driven into the sand. (Figure 1). In 1980, with the shelters in place, no kestrels or harriers were seen hunting within the tern colonies, although they were present in the vicinity.

A study by Jenks-Jay (1982) found that at seven least tern Sternula antillarum colonies on Nantucket Island, Massachusetts, USA, predation of chicks by raptors (American kestrel Falco sparverius and Northern harrier Circus hudsonius) was greatly reduced following the provision of chick shelters. The shelters were 43 cm high cones made from 11 repurposed snow fence slats with a 66 cm basal diameter placed around a stake driven into the sand. (Figure 1). In 1980, with the shelters in place, no kestrels or harriers were seen hunting within the tern colonies, although they were present in the vicinity.

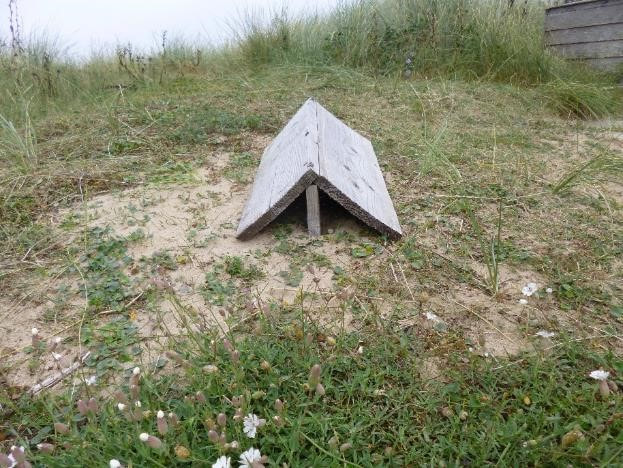

Figure 2. One of the simple chick shelters used from (Burness & Morris 1992)

Figure 2. One of the simple chick shelters used from (Burness & Morris 1992)

On a mammal-free offshore breakwater in Lake Erie, Canada (Burness & Morris 1992) observed that 10 common tern Sterna hirundo chicks were predated by American herring gulls Larus smithsonianus or ring-billed gulls Larus delawarensis and a further six disappeared for unknown reasons, in the eight days after hatching. Small wooden chick shelters, consisting of two 12.5 x 25 cm rectangles attached to form a 10 cm high triangular shelter (Figure 2) were then provided and readily adopted by the chicks. Following this no chicks were known to be predated and five disappeared over the next 12 day period (chick age could potentially also have been a factor in this study).

Figure 3. The wooden chick shelters from Butcher et al. (2007), which appear to have been unweighted and prone to blowing over.

Figure 3. The wooden chick shelters from Butcher et al. (2007), which appear to have been unweighted and prone to blowing over.

By contrast, Butcher et al. (2007) found that least tern chicks on warehouse roofs in Texas did not use artificial structures (wooden chick shelters or artificial plants) to hide from predators more than would be expected by chance, although artificial plants were used for shade. Chicks used artificial structures on 18% of the 39 occasions that the adults mobbed predators, either by running to them (twice) or remaining under them (five times) more often freezing or running away. However, the shelters provided were affected by the wind and blew over on multiple occasions suggesting they may not have provided adequate protection from predators.

Case Studies

Little tern chick shelter review from the EU LIFE+ Nature Little Tern Project

Little terns in the UK nest in open habitats, but chicks often move to vegetated areas if available a few days after hatching. In a technical note (Rendell-Read 2018) the EU LIFE+ Nature Little Tern Recovery Project conducted a review of little tern chick shelter use, which varied widely, as did the design of shelters, including boxes, simple A-frames, and pipes. Providing two entry/exit points to allow escape from a predator was a common feature.

Shelters were usually spaced out over a nesting site and it was suggested that camouflage by painting or with stones and sand could be useful, or alternatively using a variety of designs to avoid recognition by predators. Shelters should be positioned at an angle away from the prevailing wind to maximise protection, rather than creating a wind tunnel.

Little tern chick shelter review from the EU LIFE+ Nature Little Tern Project

Little terns in the UK nest in open habitats, but chicks often move to vegetated areas if available a few days after hatching. In a technical note (Rendell-Read 2018) the EU LIFE+ Nature Little Tern Recovery Project conducted a review of little tern chick shelter use, which varied widely, as did the design of shelters, including boxes, simple A-frames, and pipes. Providing two entry/exit points to allow escape from a predator was a common feature.

Shelters were usually spaced out over a nesting site and it was suggested that camouflage by painting or with stones and sand could be useful, or alternatively using a variety of designs to avoid recognition by predators. Shelters should be positioned at an angle away from the prevailing wind to maximise protection, rather than creating a wind tunnel.

RSPB Coquet Island: vegetation-suppressing chick shelters

On Coquet Island, Northumberland, England, vigorous vegetation growth in the common tern breeding areas behind the roseate tern terraces was limiting open areas available to breeding common terns and pushing them towards the roseate tern terrace. In wet weather common tern chicks were also getting wet from the dense grass, causing chilling. To create gaps in the vegetation an innovative combined chick-shelter and vegetation-supressor was trialled. These consisted of heavy board bases with elevated chick shelters running along the middle, and were deployed early in the season while the grass was still short.

The design of the vegetation-suppression shelters consisted of a large Formica tray which could be filled with sand or shingle topped with a peak roofed shelter (Formica was used because that was the material available to the organisation which built and donated the shelters). However, their construction and weight made them awkward to deploy, move and store.

In 2020, Coquet is instead using interlocking plastic paving slabs (of the type used under some of the Coquet roseate tern terraces) covered in shingle to supress the vegetation, in combination with a more traditional chick shelter as a lighter weight and more flexible option.

On Coquet Island, Northumberland, England, vigorous vegetation growth in the common tern breeding areas behind the roseate tern terraces was limiting open areas available to breeding common terns and pushing them towards the roseate tern terrace. In wet weather common tern chicks were also getting wet from the dense grass, causing chilling. To create gaps in the vegetation an innovative combined chick-shelter and vegetation-supressor was trialled. These consisted of heavy board bases with elevated chick shelters running along the middle, and were deployed early in the season while the grass was still short.

The design of the vegetation-suppression shelters consisted of a large Formica tray which could be filled with sand or shingle topped with a peak roofed shelter (Formica was used because that was the material available to the organisation which built and donated the shelters). However, their construction and weight made them awkward to deploy, move and store.

In 2020, Coquet is instead using interlocking plastic paving slabs (of the type used under some of the Coquet roseate tern terraces) covered in shingle to supress the vegetation, in combination with a more traditional chick shelter as a lighter weight and more flexible option.

Where both vegetation-supression and chick shelter provision are desirable, this design could perhaps be useful if it were improved by lowering the shelters; a height of about 5cm is all that is needed for chicks. Overly high shelters allow both predator access and rain/wind ingress, significantly reducing the value of the shelter.

High shelters may also deter terns from nesting in the area as most terns prefer an open aspect which gives good views of any approaching predators. As can be seen in Figure 7, the roofs on these shelters are within the eyeline of an adult tern, even more so if it was sitting on a nest.

Lighter-weight bases should also be considered if the shelters have to be moved, although they must then be weighted or anchored to ensure they cannot be lifted by the wind.

High shelters may also deter terns from nesting in the area as most terns prefer an open aspect which gives good views of any approaching predators. As can be seen in Figure 7, the roofs on these shelters are within the eyeline of an adult tern, even more so if it was sitting on a nest.

Lighter-weight bases should also be considered if the shelters have to be moved, although they must then be weighted or anchored to ensure they cannot be lifted by the wind.

Chick shelters on tern rafts and artificial structures

Rafts and artificial structures for terns often lack vegetation, so chick shelters are commonly used.

Shelters can be positioned at the start of the season, distributed across the surface, or deployed once the chicks have hatched, in which case they are usually placed close to each nest. The choice of strategy adopted will depend on the practicality and the extent of disturbance caused in deploying the shelters.

Rafts and artificial structures for terns often lack vegetation, so chick shelters are commonly used.

Shelters can be positioned at the start of the season, distributed across the surface, or deployed once the chicks have hatched, in which case they are usually placed close to each nest. The choice of strategy adopted will depend on the practicality and the extent of disturbance caused in deploying the shelters.

Figure 8. A tern raft at West Hayling Local Nature Reserve (part of RSPB Langstone Harbour) on the south coast of England, showing the mesh fencing to keep unfledged chick out of the water and the plywood chick shelters added once common tern chicks have hatched with rock weights used to keep them stable and in place (Wez Smith; RSPB).

Relevant sections of Conservation Evidence

Action: Physically protect nests with individual exclosures/barriers or provide shelters for chicks of ground nesting seabirds

Action: Physically protect nests with individual exclosures/barriers or provide shelters for chicks of ground nesting seabirds

References

Burness G.P & Morris R.D. (1992) Shelters decrease gull predation on chicks at a common tern colony. Journal of Field Ornithology, 63, 186-189

Butcher J.A., Neill R.L. & Boylan J.T. (2007) Survival of least tern chicks hatched on gravel-covered roofs in north Texas. Waterbirds, 30, 595-601

Jenks-Jay N. (1982) Chick shelters decrease avian predation in least tern colonies on Nantucket Island, Massachusetts. Journal of Field Ornithology, 53, 58-60

Rendell-Read S. (2018) EU LIFE+ Nature Little Tern Recovery Project Technical Note 2 Chick Shelters ISSUE 1.0. Unpublished technical note.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Paul Morrison (RSPB, Coquet Island) and Steve Newton (Birdwatch Ireland) for information on the use of chick shelters.

Burness G.P & Morris R.D. (1992) Shelters decrease gull predation on chicks at a common tern colony. Journal of Field Ornithology, 63, 186-189

Butcher J.A., Neill R.L. & Boylan J.T. (2007) Survival of least tern chicks hatched on gravel-covered roofs in north Texas. Waterbirds, 30, 595-601

Jenks-Jay N. (1982) Chick shelters decrease avian predation in least tern colonies on Nantucket Island, Massachusetts. Journal of Field Ornithology, 53, 58-60

Rendell-Read S. (2018) EU LIFE+ Nature Little Tern Recovery Project Technical Note 2 Chick Shelters ISSUE 1.0. Unpublished technical note.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Paul Morrison (RSPB, Coquet Island) and Steve Newton (Birdwatch Ireland) for information on the use of chick shelters.