Citation: Babcock and Booth (2020) Habitat: Rafts and Structures. Tern Conservation Best Practice. Produced for “Improving the conservation prospects of the priority species roseate tern throughout its range in the UK and Ireland” LIFE14 NAT/UK/000394’

Last updated: October 2020

This is a live document we update regularly. If you have comments and suggestions, please email Chantal.Macleod-Nolan@rspb.org.uk

Last updated: October 2020

This is a live document we update regularly. If you have comments and suggestions, please email Chantal.Macleod-Nolan@rspb.org.uk

| Babcock and Booth (2020) Habitat: Rafts and Structures. Tern Conservation Best Practice. | |

| File Size: | 3359 kb |

| File Type: | |

Key Messages

- A raft or nesting structure in the right location can be a valuable tool for tern conservation, providing nesting opportunities where the water is too deep to create islands and as part of a network of potential breeding sites.

- Rafts require ongoing commitment of staff time and funds for maintenance and vigilance to ensure they are protected from any emerging threats e.g. changing predation pressures. Not all tern species will use rafts.

- Structures, particularly flat, gravelled rooftops have been adapted for nesting tern species around the world, although they are not used by all tern species.

- Providing nesting habitat is most successful near to existing colonies and foraging areas. Many successful colonies persist for years but then decline or abandon in response to changing pressures such as predation or disturbance affecting productivity. It is important to have alternative sites available.

Information

Use of rafts and artificial structures to create tern nesting habitat is a long-established management technique, particularly for common terns Sterna hirundo (Burgess & Hirons, 1992). Rafts are rarely used by other tern species. As well as providing breeding habitat in areas where this might be lacking, tern rafts or structures in areas frequented by the public like Preston Docks or Port Edgar marina are also a useful opportunity to raise public awareness and talk about these species.

Before starting a raft or nesting structure project, consider whether the location has any risks associated with natural coastal processes or climate change, disturbance by people, or predation from native or non-native mammals or birds. If a raft is moored near boats, it needs to be insured against third party damage and to have a marine licence.

To be successful a raft or structure must be located within the foraging distance of a good food source and the presence of piscivorous birds already feeding in the area is a good indication of this. Rafts in the UK will be most commonly used by common terns Sterna hirundo, black-headed gulls Chroicocephalus ridibundus and lesser black-backed gulls Larus fuscus. If a raft is intended to benefit terns but there are other species present which may colonise before the terns arrive, then consider a delayed deployment or a covering, for example with a tarpaulin, until the terns arrive and begin prospecting.

Rafts need ongoing maintenance such as repairs to any structural damage, removal of excess vegetation and replenishing shingle, and this and the associated costs must be factored in to any plans to deploy rafts. There is often an opportunity to carry out this work in winter as in most cases rafts are not left in position all year, but either floated to a safe winter location or brought on land. Means to bring the raft in are required and perhaps also storage space. The most successful results will often arise from observing the way the raft or structure is used, and making changes to optimise the habitat, position, timing size or other variables, for the specific location and species.

Use of rafts and artificial structures to create tern nesting habitat is a long-established management technique, particularly for common terns Sterna hirundo (Burgess & Hirons, 1992). Rafts are rarely used by other tern species. As well as providing breeding habitat in areas where this might be lacking, tern rafts or structures in areas frequented by the public like Preston Docks or Port Edgar marina are also a useful opportunity to raise public awareness and talk about these species.

Before starting a raft or nesting structure project, consider whether the location has any risks associated with natural coastal processes or climate change, disturbance by people, or predation from native or non-native mammals or birds. If a raft is moored near boats, it needs to be insured against third party damage and to have a marine licence.

To be successful a raft or structure must be located within the foraging distance of a good food source and the presence of piscivorous birds already feeding in the area is a good indication of this. Rafts in the UK will be most commonly used by common terns Sterna hirundo, black-headed gulls Chroicocephalus ridibundus and lesser black-backed gulls Larus fuscus. If a raft is intended to benefit terns but there are other species present which may colonise before the terns arrive, then consider a delayed deployment or a covering, for example with a tarpaulin, until the terns arrive and begin prospecting.

Rafts need ongoing maintenance such as repairs to any structural damage, removal of excess vegetation and replenishing shingle, and this and the associated costs must be factored in to any plans to deploy rafts. There is often an opportunity to carry out this work in winter as in most cases rafts are not left in position all year, but either floated to a safe winter location or brought on land. Means to bring the raft in are required and perhaps also storage space. The most successful results will often arise from observing the way the raft or structure is used, and making changes to optimise the habitat, position, timing size or other variables, for the specific location and species.

Raft Design

There are various raft designs and the appropriate one will depend on the challenges of the particular location and budget, for example, a raft on sheltered lagoon need not be as robust as one in an exposed marine environment. All consist of some form of flotation and a substrate-covered platform, floatation can be provided by for example, polystyrene blocks, air-filled barrels or jetfloats, and a tether to stop the raft moving. Where water levels fluctuate the tether length and method must accommodate the full likely range of water levels. If the lowest water level might lead the the raft sitting on the bottom, the base must be strong enough to support the raft without damaging the floats. Detailed information on the construction and design of rafts can be found at: RSPB and BTO, but there remains scope for originality and innovation.

The size of rafts is an important factor in their success. By linking jetfloats into fewer larger islands, RSPB Dungeness established a larger common tern colony which was better able to defend itself against avian predators. However, a larger raft is also more affected by torque i.e. twisting forces created by wind and wave action, so this may limit the size of rafts possible, particularly in exposed sites. On Loch Creran, Scotland, old mussel rafts were repurposed to create robust tern rafts suitable for an exposed location.

Fencing the edge of a raft or platform prevents chicks falling in the water, as unfledged birds will be unable to climb back on (in a natural situation they would not be exposed to deep water in this way), another way to mitigate this is by fitting a hinged flap to the edge of the raft, providing a shallow gradient which can be climbed (floatation such as a sealed length of PVC pipe can act as flotation device to ensure the hinged section remains in position). Additionally, a rescue platform for newly fledged chicks, (which can get airborne before they are fully waterproof) is sometimes provided, consisting of a low platform in the water next to the raft onto which fledglings can climb. These shelves and ramps are not suitable for sites with a risk of mammalian predation.

Where mammalian predators may swim out to a raft protective barriers can be fitted. Mink-proof barriers are usually a clear polycarbonate screen with a smooth surface that offers no footholds for the animals to climb. When designing these, it is important to consider whether it will be necessary how to safely get onto the raft from a boat, for example by including a section of the barrier that can be easily opened or removed. The mooring of a raft should also avoid providing opportunities for predators to climb from the water onto the raft, and must be sufficient to allow the raft to float with the maximum range of water level fluctuations without tipping or flooding the raft. Canes have been used on rafts to deter avian predators.

Suitable substrate for nesting terns is unvegetated or sparsely vegetated shingle (Richards and Morris, 1984). It is important that drainage is incorporated into the platform so that that substrate does not become saturated and causing eggs and chicks to chill. It may be helpful to physically divide larger platforms into smaller sections to keep the material evenly distributed, but bear in mind that nesting sites against an edge are attractive to black-headed gulls. Where there isn’t natural shelter such as vegetation then chick shelters (which provide an element of protection from the elements and predators) should be provided.

Where there is no nearby colony, decoys and audio lures can aid colonisation. It is not unusual for the first nesting attempts on a new raft to be late in the season, when pairs may be searching for alternative nest sites after a failure of a first breeding attempt. If there are large areas of apparently suitable natural habitat nearby terns are likely to continue to prefer this, even if it is subject to flooding or predation (as in the Solent).

There are various raft designs and the appropriate one will depend on the challenges of the particular location and budget, for example, a raft on sheltered lagoon need not be as robust as one in an exposed marine environment. All consist of some form of flotation and a substrate-covered platform, floatation can be provided by for example, polystyrene blocks, air-filled barrels or jetfloats, and a tether to stop the raft moving. Where water levels fluctuate the tether length and method must accommodate the full likely range of water levels. If the lowest water level might lead the the raft sitting on the bottom, the base must be strong enough to support the raft without damaging the floats. Detailed information on the construction and design of rafts can be found at: RSPB and BTO, but there remains scope for originality and innovation.

The size of rafts is an important factor in their success. By linking jetfloats into fewer larger islands, RSPB Dungeness established a larger common tern colony which was better able to defend itself against avian predators. However, a larger raft is also more affected by torque i.e. twisting forces created by wind and wave action, so this may limit the size of rafts possible, particularly in exposed sites. On Loch Creran, Scotland, old mussel rafts were repurposed to create robust tern rafts suitable for an exposed location.

Fencing the edge of a raft or platform prevents chicks falling in the water, as unfledged birds will be unable to climb back on (in a natural situation they would not be exposed to deep water in this way), another way to mitigate this is by fitting a hinged flap to the edge of the raft, providing a shallow gradient which can be climbed (floatation such as a sealed length of PVC pipe can act as flotation device to ensure the hinged section remains in position). Additionally, a rescue platform for newly fledged chicks, (which can get airborne before they are fully waterproof) is sometimes provided, consisting of a low platform in the water next to the raft onto which fledglings can climb. These shelves and ramps are not suitable for sites with a risk of mammalian predation.

Where mammalian predators may swim out to a raft protective barriers can be fitted. Mink-proof barriers are usually a clear polycarbonate screen with a smooth surface that offers no footholds for the animals to climb. When designing these, it is important to consider whether it will be necessary how to safely get onto the raft from a boat, for example by including a section of the barrier that can be easily opened or removed. The mooring of a raft should also avoid providing opportunities for predators to climb from the water onto the raft, and must be sufficient to allow the raft to float with the maximum range of water level fluctuations without tipping or flooding the raft. Canes have been used on rafts to deter avian predators.

Suitable substrate for nesting terns is unvegetated or sparsely vegetated shingle (Richards and Morris, 1984). It is important that drainage is incorporated into the platform so that that substrate does not become saturated and causing eggs and chicks to chill. It may be helpful to physically divide larger platforms into smaller sections to keep the material evenly distributed, but bear in mind that nesting sites against an edge are attractive to black-headed gulls. Where there isn’t natural shelter such as vegetation then chick shelters (which provide an element of protection from the elements and predators) should be provided.

Where there is no nearby colony, decoys and audio lures can aid colonisation. It is not unusual for the first nesting attempts on a new raft to be late in the season, when pairs may be searching for alternative nest sites after a failure of a first breeding attempt. If there are large areas of apparently suitable natural habitat nearby terns are likely to continue to prefer this, even if it is subject to flooding or predation (as in the Solent).

Structures

Provision of nesting habitat on artificial structures can provide additional habitat for colonies in areas where natural habitat is limited, disturbed and/or dominated by other species, and provides an alternative to natural sites that are vulnerable to flooding, human disturbance or ground predators.

In many cases existing structures have been adopted or adapted for terns. Rooftops in Japan (Hayashi et al. 2002) are used by little terns Sternula albifrons. In Florida, least terns Sterna antillarum have nested on rooftops since the 1950’s (Warraich et al. 2012) and gull-billed terns Gelochelidon nilotica since 1995 (Gore et al. 2008). Elsewhere in the USA least terns in Georgia and common terns in North Carolina (Cameron 2008) have been reported as nesting on roofs. Common terns were encouraged to nest on a flat roof by Lake Zurich in 2015 and bred successfully (Knaus et al. 2018).

In Montrose, Scotland a colony of Arctic terns Sterna paradisaea settled on a factory roof, but a raft was deployed as an alternative nesting site, as factory-workers were being attacked by terns defending their nests.

In Dublin Port, four structures, two pontoons and two dolphins (large wooden structures with a concrete or metal platform, rather than the cetaceans) support colonies of common and Arctic terns.

In Portugal, Catry et al. 2004 reports that most of the little tern population now nests in salinas (artificial salt pans) while in Spain the importance of this man-made habitat has been recognised with a LIFE project to benefit Audouin’s gull Ichthyaetus audouinii and seven other wetland bird species (including four tern species).

Provision of nesting habitat on artificial structures can provide additional habitat for colonies in areas where natural habitat is limited, disturbed and/or dominated by other species, and provides an alternative to natural sites that are vulnerable to flooding, human disturbance or ground predators.

In many cases existing structures have been adopted or adapted for terns. Rooftops in Japan (Hayashi et al. 2002) are used by little terns Sternula albifrons. In Florida, least terns Sterna antillarum have nested on rooftops since the 1950’s (Warraich et al. 2012) and gull-billed terns Gelochelidon nilotica since 1995 (Gore et al. 2008). Elsewhere in the USA least terns in Georgia and common terns in North Carolina (Cameron 2008) have been reported as nesting on roofs. Common terns were encouraged to nest on a flat roof by Lake Zurich in 2015 and bred successfully (Knaus et al. 2018).

In Montrose, Scotland a colony of Arctic terns Sterna paradisaea settled on a factory roof, but a raft was deployed as an alternative nesting site, as factory-workers were being attacked by terns defending their nests.

In Dublin Port, four structures, two pontoons and two dolphins (large wooden structures with a concrete or metal platform, rather than the cetaceans) support colonies of common and Arctic terns.

In Portugal, Catry et al. 2004 reports that most of the little tern population now nests in salinas (artificial salt pans) while in Spain the importance of this man-made habitat has been recognised with a LIFE project to benefit Audouin’s gull Ichthyaetus audouinii and seven other wetland bird species (including four tern species).

Research

Dunlop et al. (1991) reported that at a common tern colony in Canada four rafts (5 x 5 m, covered with sand and gravel, each with six decoy terns) were used in the first year and had an average productivity of 1.3 fledglings/nests). The raft deployed closest to the common tern loafing area was colonised first; two rafts deployed closest to a ring-billed gull Larus delawarensis colony were not colonised until they had been moved further from the gull colony. It was noted that birds appeared to have difficulty relocating their nests after the accidental rotation of one of the rafts by 90 degrees when it had been moved by a storm.

Dunlop et al. (1991) reported that at a common tern colony in Canada four rafts (5 x 5 m, covered with sand and gravel, each with six decoy terns) were used in the first year and had an average productivity of 1.3 fledglings/nests). The raft deployed closest to the common tern loafing area was colonised first; two rafts deployed closest to a ring-billed gull Larus delawarensis colony were not colonised until they had been moved further from the gull colony. It was noted that birds appeared to have difficulty relocating their nests after the accidental rotation of one of the rafts by 90 degrees when it had been moved by a storm.

Case Studies

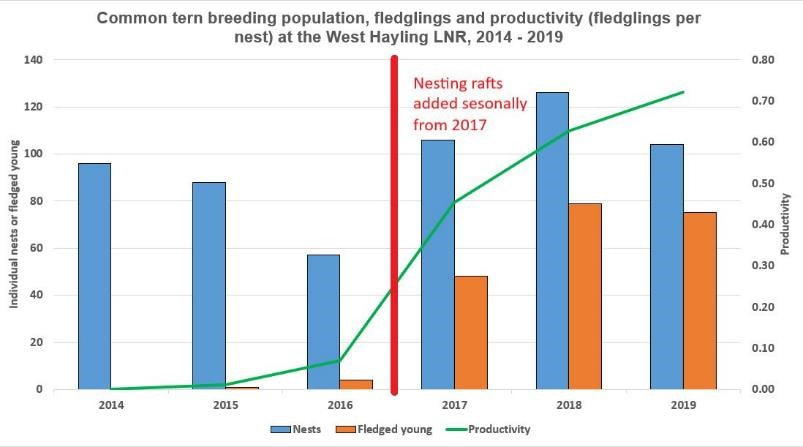

West Hayling Local Nature Reserve, RSPB Langstone Harbour: a lagoon raft to increase habitat

At RSPB-managed West Hayling Local Nature Reserve on the south coast of England, a raft was used to provide additional breeding habitat in a tidal lagoon historically used for the cultivation of oysters. Seabirds on the Oysterbeds bred on the linear islets in the lagoon created when the bunds were severed, which offered an area relatively free from disturbance or ground predators. However, common terns were being displaced by black-headed gulls, which arrive on the site earlier in the breeding season and occupy the habitat. Common tern pair numbers declined, and productivity was very low, as tern nests around the periphery of the gull colony were susceptible to predation by the gulls.

A raft was built by a local carpenter in four sections each consisting of a wooden platform over plastic drum floats. These were bolted together while in operation, but the sectional design made construction and storage simpler. A wire mesh fence around the edge allows observations of the raft from the shore while preventing chicks from falling into the water, and a platform on the edge gives fledglings a loafing area.

West Hayling Local Nature Reserve, RSPB Langstone Harbour: a lagoon raft to increase habitat

At RSPB-managed West Hayling Local Nature Reserve on the south coast of England, a raft was used to provide additional breeding habitat in a tidal lagoon historically used for the cultivation of oysters. Seabirds on the Oysterbeds bred on the linear islets in the lagoon created when the bunds were severed, which offered an area relatively free from disturbance or ground predators. However, common terns were being displaced by black-headed gulls, which arrive on the site earlier in the breeding season and occupy the habitat. Common tern pair numbers declined, and productivity was very low, as tern nests around the periphery of the gull colony were susceptible to predation by the gulls.

A raft was built by a local carpenter in four sections each consisting of a wooden platform over plastic drum floats. These were bolted together while in operation, but the sectional design made construction and storage simpler. A wire mesh fence around the edge allows observations of the raft from the shore while preventing chicks from falling into the water, and a platform on the edge gives fledglings a loafing area.

The raft was launched in early April 2017, after the majority of black-headed gulls had arrived, and kept covered by a tarpaulin to further discourage black-headed gulls (see also Shotton, below, and Lampman et.al., 1996, where a cover was used to discourage ring-billed gulls). The cover was partially removed in late April (at which point common and little tern decoys were placed on the raft), and completely removed in early May. Common terns showed interest almost immediately and were incubating eggs by 18 May. Once the chicks had hatched chick shelters were added near each nest.

By the end of its first season 44 chicks had fledged from the raft, despite challenging weather, (compared to five from the island between 2014 and 2016), success which has been repeated in subsequent years. By not making the raft habitat available until the common terns are ready to nest they are able to breed in the dense colony which can be effectively defended from avian predators. In 2018, an experimental small raft made from a pallet floating on plastic bottles in metal gabion cages was launched partway through the season and used very quickly (Smith 2018a); while in 2019 a supplemental raft built by a local scout troop was deployed a week later than the main raft and used almost immediately. The West Hayling rafts are stored on shore, above the storm surge line, over the winter.

By the end of its first season 44 chicks had fledged from the raft, despite challenging weather, (compared to five from the island between 2014 and 2016), success which has been repeated in subsequent years. By not making the raft habitat available until the common terns are ready to nest they are able to breed in the dense colony which can be effectively defended from avian predators. In 2018, an experimental small raft made from a pallet floating on plastic bottles in metal gabion cages was launched partway through the season and used very quickly (Smith 2018a); while in 2019 a supplemental raft built by a local scout troop was deployed a week later than the main raft and used almost immediately. The West Hayling rafts are stored on shore, above the storm surge line, over the winter.

Lymington-Keyhaven Nature Reserve and North Solent: rafts for colonies in new areas

In 2017, the same year that the West Hayling Oysterbeds raft was first launched, eight partially fabricated recycled plastic tern rafts were purchased from Filcris, and deployed on saline lagoons on the south coast of England, six at Lymington-Keyhaven Nature Reserve and four at North Solent National Nature Reserve. Each raft measured 1.22m x 2.44m and cost around £840 each

The rafts saw interest from terns but did not attract breeding birds in their first couple of years in contrast to the success of the West Hayling raft, which was both adjacent to an existing colony and larger. The Lymington-Keyhaven the raft locations were away from the primary colony areas and feeding zones. The higher availability of apparently suitable ‘natural’ habitat in the north-west Solent (although vulnerable to high tides and predators) may also prove more attractive to terns .

In 2019, eight rafts (instead of four) were deployed at North Solent National Nature Reserve and some of the substrate changed from pumice to a more natural selection of sand and shingle. Although the rafts attracted black-headed gulls, four pairs of common terns nested on one of them, preferring the natural substrate to the pumice.

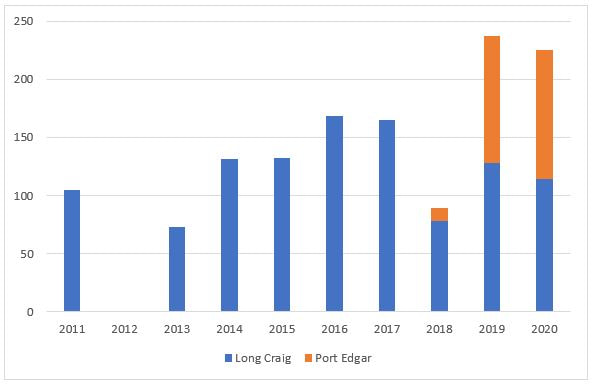

Port Edgar Tern Raft, Queensferry: replacing habitat lost to large gulls

The Firth of Forth, in Scotland used to be the main breeding area for roseate terns in Scotland; however, due to increased competition for nesting areas and predation from large gulls, they have not been recorded breeding at any of the Forth islands since their departure from Long Craig Island in 2009. Coinciding with the expansion of large gulls, common terns also abandoned their former strongholds on Inchmickery, Fidra and other islands and moved to Leith Docks SPA, Long Craig and the Isle of May. An initial review of management options for the Forth Island SPA concluded that the scope for creating gull-free zones on the RSPB managed islands of Inchmickery and Fidra (something that had been attempted previously but without success) was limited, based on previous experience, the number of nesting gulls, and the conservation status of the large gull species. Options for other sites in the Firth of Forth were limited; as were opportunities at the Leith Docks common tern colony (a separate SPA).

Since Long Craig suffered from infrequent flooding, the Roseate Tern LIFE Project sought to support the colony by creating an additional/ back-up site to boost the numbers of the common terns with which roseate terns often associate. The assessment of management options identified Port Edgar marina as a site where conservation measures could be implemented. Before the 2018 breeding season the LIFE Project deployed an 8 x 8 m square raft in a quiet area of the Marina (1.5 km away from Long Craig). The raft, sourced from Kames Pontoons Jetties and Nesting Rafts replaced an old pontoon, which supported a small number of common terns, but had been badly damaged in the winter storms of 2014/15.

In its first season, the Port Edgar raft supported a peak count of 11 common tern nests and 13 chicks fledged. In addition, more birds were observed arriving after high tides and the noise disturbance at Long Craig (Knowles 2018).

In spring 2019, anti-predator canes were added to the raft to deter gulls from colonising the raft before the terns and from subsequently predating tern eggs and chicks. The barrier to stop pre-fledged chicks from going overboard was also raised with a mesh encircling the raft. In 2019 there was a peak count of 109 AONs with 118 fledged chicks (Knowles 2019) and 111 pairs in 2020 with a minimum 58 chicks hatched. Several incidents of entanglement in the geotextile fabric on the raft were recorded, requiring modification before the next season. The Port Edgar raft is bought in and moored against a jetty to protect it from winter conditions.

In spring 2019, anti-predator canes were added to the raft to deter gulls from colonising the raft before the terns and from subsequently predating tern eggs and chicks. The barrier to stop pre-fledged chicks from going overboard was also raised with a mesh encircling the raft. In 2019 there was a peak count of 109 AONs with 118 fledged chicks (Knowles 2019) and 111 pairs in 2020 with a minimum 58 chicks hatched. Several incidents of entanglement in the geotextile fabric on the raft were recorded, requiring modification before the next season. The Port Edgar raft is bought in and moored against a jetty to protect it from winter conditions.

RSPB Dungeness, England: choosing the right raft design for local conditions

At RSPB Dungeness, on the south coast of England, tern rafts were created using a branded modular plastic product called Jetfloat for floatation topped with a wooden platform and secured with ropes; the wooden platform was covered with a membrane and aggregate. The modular nature of the product meant that it was easy to experiment with rafts of different sizes, and it was discovered that that a larger raft was more successful than several smaller ones, as the common terns were better able to defend the colony.

However, the light weight and high buoyancy of the Jetfloat (which is designed to be capable of supporting much heavier loads) meant that the rafts were easily buffeted by the strong winds at this exposed site. Ultimately the rafts were replaced by heavier duty rafts sourced from the Kames (the company which supplied the Port Edgar Marina raft). This was more expensive but better suited to the local conditions and were more successful. The rafts at Dungeness are in addition to the island restoration work in Burrowes Pit.

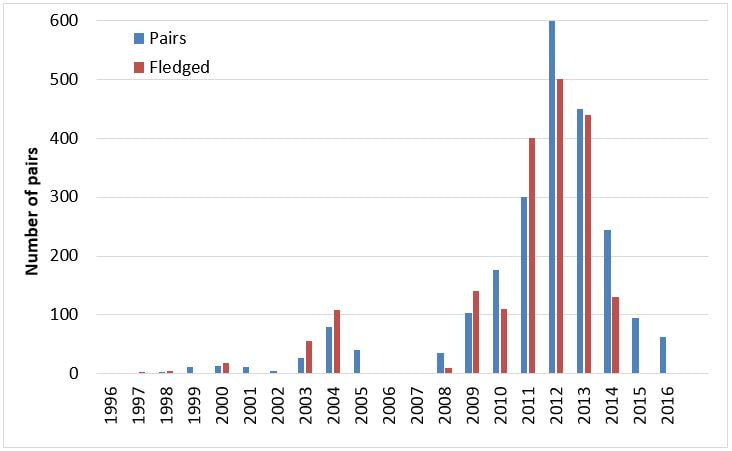

Mussel Rafts in Loch Creran, Scotland: adapted mussel rafts with mink-proof fences

At South Shian, Loch Creran, a sea loch in Argyll, Scotland, common tern nesting rafts were created from rafts originally used for mussel farming, initially alongside the farming operation and later after mussel farming had ceased. Common terns had previously bred on an island in the Loch but abandoned the colony in the 1980s due to predation by feral mink. They continued to return to the area each year, but never settled. Local ornithologist, Dr Clive Craik worked with the mussel farmer to create a nesting area on one of the rafts, initially with a sheet of plywood and some grassy turves, which attracted a single pair in its first year, 1996. Over time the area of nesting habitat was expanded, fenced to prevent chicks falling into the sea and predator-proofed to exclude both otters and mink (Craik 2013). In the 2000s mussel farming was discontinued and eventually the structures were licensed as standalone tern rafts.

The structure consisted of four mussel rafts, moored together as one unit, three were floored with marine plywood as tern breeding habitat, while one was a “socialising” raft (considered important for the terns throughout the breeding season in the absence of other places to land). The breeding area on each raft was 12.2m x 12.2 m.

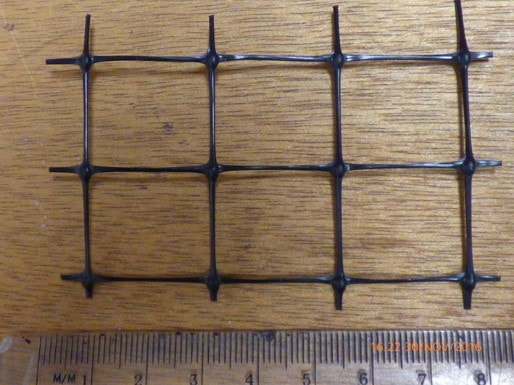

Each breeding raft is fenced with a plastic mesh (22 x 20 mm) fence just short of 1 m height to prevent unfledged young of all sizes from jumping into the water if panicked. The height was chosen because the mesh came in rolls 2 m wide, which were cut in half, with a small lip at the bottom stapled to the raft surface, but exceeds the height needed to stop tern chicks.

The fences also served as a barrier to two of the main predators of tern chicks in this area, mink and otters. Additionally, mink were trapped by incorporating a mink-trap into the fence (perpendicular to the fence) meaning that the easiest route for a mink to get onto a raft is by entering a trap. This method caught mink much more successfully than randomly sited, baited mink-traps. Predation by peregrines remained an issue.

After observing a number of newly-fledged terns, just capable of flight, landing on the water and being unable to take off again, pallets were provided at the edge of the rafts to provide a resting area for fledglings. Later pallets were lashed to the rafts at an angle, to enable fledglings to climb back up onto the rafts.

Common tern numbers on the Loch Creran rafts grew from a single pair in 1996 to a peak of 600 pairs in 2012, although numbers and productivity could be variable, and the colony was deserted after a mink attack in 2005. In subsequent years food shortages and peregrine predation affected productivity severely, so there was almost no successful breeding after 2015. The rafts were dismantled in the spring of 2019.

After observing a number of newly-fledged terns, just capable of flight, landing on the water and being unable to take off again, pallets were provided at the edge of the rafts to provide a resting area for fledglings. Later pallets were lashed to the rafts at an angle, to enable fledglings to climb back up onto the rafts.

Common tern numbers on the Loch Creran rafts grew from a single pair in 1996 to a peak of 600 pairs in 2012, although numbers and productivity could be variable, and the colony was deserted after a mink attack in 2005. In subsequent years food shortages and peregrine predation affected productivity severely, so there was almost no successful breeding after 2015. The rafts were dismantled in the spring of 2019.

Langstone Harbour ‘Tern Table’: an experimental approach to creating extra nesting habitat

At RSPB Langstone Harbour, the increasing number of seabirds in the colony (which in 2018 experienced an influx of over 1700 breeding pairs of Mediterranean gulls Larus melanocephalus was thought to be pushing terns into less suitable areas of breeding habitat where they were vulnerable to high tides. Following the success of the tern raft projects locally, it seemed likely that additional habitat would also be valuable on the main islands in the harbour, however both the saltmarsh vegetation on the islands and surrounding mud are designated. An ingenious solution the ‘tern table’ was proposed by Site Manager Wez Smith, and consent was given by Natural England. This is a temporary structure, essentially a raft on legs, providing a gravel-topped platform elevated above the saltmarsh allowing light to reach the vegetation and high tide floods to pass underneath. The edge is fenced to prevent unfledged chicks falling off, and the structure is held in place by its own weight, (including that of the gravel) plus the two seaward legs being secured to shingle-filled gabions.

In the first and second seasons the tern table has been occupied by an oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus pair, however there is potential to develop this approach further and it may yet prove useful for breeding terns (Smith 2018b).

Lymington Breakwater Bunds, England: an attempt to create a new colony site on existing structures

In March 2017, three nesting bunds were created on the eastern breakwater in Lymington River on the south coast of England. The breakwater, which protects Lymington harbour from erosion, was identified as being suitable for nesting terns being free from ground predators and/or human disturbance.

A local wetland restoration company won the tender to construct the bunds. It took four days to construct the bunds, which were fabricated using hessian sandbags filled with postcrete. Gaps between the rock revetments were filled in with sandbags to form a level nesting area which was reinforced with stainless steel pins. The hessian will wear away with time, leaving behind a solid concrete structure. The cost of the three nesting bunds was approximately £8,700 + VAT, including cost of labour, equipment, machinery and materials.

A pair of common terns were regularly seen on one of the nesting bunds during the 2017 season but no nests were recorded. A pair of oystercatchers built a nest on the central bund, which was predated, probably by the great black-backed gull Larus marinus pair which also nested on the breakwater. In the following year, a pair of peregrine falcon Falco peregrinus nested on one of the bunds. The combination of territorial oystercatcher, peregrine falcons and nesting gulls may have been sufficient to deter terns from nesting. At the time of writing (2020) the bunds have not been used by breeding terns. It is notable that the nesting areas are small and not near an existing tern colony.

Shotton Lagoon Rafts, England: islands created from bunds

The management by Merseyside Ringing Group (MRG) of the lagoons at Shotton Steelworks adjacent to the River Dee and near the Dee Estuary in northwest England shows the evolution of a managed colony using artificial structures. The lagoons were originally used to circulate and cool clean water from blast furnace operations; they ceased in the 1970s and the area was designated as a SSSI. The first nesting rafts for common terns were provided in 1970, and the tern colony quickly expanded. To create more space, and reduce maintenance, a more permanent platform was created in 1973 with a scaffold framework, a plank base covered with steelworks slag, and wooden sides.

Water penetration from both above and below the rafts and platform led to deterioration in their condition over a relatively short period of years so MRG realised that the only viable long-term solution was to create an island, which also offered the possibility of creating a much larger nesting area. In 1987, an island was created by cutting through an existing bund, creating a substrate with sea sand, stabilising the banks with concrete and creating sides and dividers from corrugated iron. That year terns preferred to remain on the island, where they had nested previously. The following year the island was resurfaced with slag, the platform was removed and there were 191 nests on the island. A second island was island created in 1994 and a third in 2000. The islands at Shotton are a way to provide a large area of nesting habitat but are still subject to erosion by wave action and are not maintenance free, as vegetation control in particular is required.

The colony remains subject to external factors, and was largely deserted from 2009 to 2012, possibly as a result of a reduction in local fish stocks (Smith 2015). It was also subject to fox predation in 2013 and to the rapid build-up of black-headed gull numbers after 2014. As a result, colony management have installed fox-deterrent fencing and adopted measures to reduce gull numbers on the islands including the creation of alternative habitat, covering the islands with fine debris mesh before the terns arrive (see Figure 17), laser hazing and managed control of the black-headed gull population.

One side effect of the netting has been accelerated early-season weed growth, so that spraying immediately after the removal of the netting kills off more weed growth, reducing weed cover until much later in the season.

One side effect of the netting has been accelerated early-season weed growth, so that spraying immediately after the removal of the netting kills off more weed growth, reducing weed cover until much later in the season.

Preston Dock Wave Breakers, England: an opportunistic colony with limited management access:

Preston Dock, a large former commercial dock off the River Ribble in Northwest England now used as a marina is one of two colonies in the larger Liverpool Bay meta-population that appeared after the 2009 desertion at Shotton, highlighting the importance of having alternative suitable habitat nesting available within an area.

The 37 wave breakers are low 12 x 2.5 m floats arranged in two offset lines across the dock entrance. Designed to reduce wave energy, only half the area of each is usable for nesting due to wave wash around the edges. They are made of concrete encased plastic and anchored to the dock bed and each other. Two common terns nested on bare wave breakers in 2009.

After 2009 Preston City Council (PCC), RSPB and Fylde Bird Club collaborated to provide substrate and shelter. Because the site is owned and managed by PCC all materials must be approved by PCC, and nothing ‘unsightly’ is allowed. One visit to the wave breakers is allowed each year to deploy materials, but no maintenance visits.

Because a perimeter barrier as used on rafts would defeat the purpose of the wave breakers, fully enclosed nest trays (450 mm x 300 mm and 125 mm high with a 125 mm roof at one end are deployed; they have plastic bases with drain holes and are filled with an inch of gravel (see Figure 18). Chicks which are not in trays can still fall into the water and it is proposed to install hessian ladders to help them get back out.

By 2014, 140 pairs of common terns nested on the wave breakers, fledging approximately 70 chicks. But predation by lesser black-backed gull, possibly a single specialising bird, became an issue in 2016. In 2019, 124 pairs of common terns fledged 19 chicks and 5 pairs of Arctic terns fledged 1 chick. Provided that PCC consent is forthcoming it is proposed to attempt to deploy canes in future to deter gull predation to the extent possible.

Banter See common tern colony, Wilhelmshaven, north-western Germany.

The common tern colony in the Banter See breeds on six concrete islands, each of which measures 10 x 5 m and is surrounded by a 60 cm wall, which were originally used as a loading dock for the now abandoned U-boat harbour. The colony was attracted to the site in 1984 using tape lures, after their previous breeding site had been destroyed. From an initial 90 breeding pairs the colony grew rapidly to a maximum of 530 pairs in 2005. Breeding success is highly variable, dependent on food availability in the Wadden Sea. Following several years of low breeding success, lower juvenile survival and delayed first breeding attempts, the colony was reduced to 430 pairs in 2011. This was most likely due to lack of food; Banter See terns feed mostly on juvenile herring, sprat and smelt which vary in abundance.The predation rate is low, since the islands are protected from terrestrial predators, but in some years predation by owls has been an issue.

The colony hosts a long-term study by the Institute of Avian Research Ornithologial Station Helogoland. The site is also protected as a natural monument of the city.

Relevant sections of Conservation Evidence

Action: Provide artificial nesting sites for ground and tree-nesting seabirds

Action: Physically protect nests with individual exclosures/barriers or provide shelters for chicks of ground nesting seabirds

Action: Remove vegetation to create nesting areas

Action: Use decoys to attract birds to safe areas

Action: Provide artificial nesting sites for ground and tree-nesting seabirds

Action: Physically protect nests with individual exclosures/barriers or provide shelters for chicks of ground nesting seabirds

Action: Remove vegetation to create nesting areas

Action: Use decoys to attract birds to safe areas

References

Burgess N.D. & Hirons G.J.M. (1992) Creation and management of artificial nesting sites for wetland birds. Journal of Environmental Management, 34, 285-295

Cameron S. (2008) Roof-nesting by common terns and black skimmers in North Carolina. The Chat 72 (2) 44-45

Catry T., Ramos J.A., Catry I., Allen-Revez M. and Grade N. (2004) Are salinas a suitable alternative breeding habitat for Little Terns Sterna albifrons? Ibis 146, 247-257

Craik, C. (2013) The South Shian tern rafts. Eider December 2013 (No. 106)

Dunlop C.L., Blokpoel H. & Jarvie S. (1991) Nesting rafts as a management tool for a declining common tern (Sterna hirundo) colony. Colonial Waterbirds, 14, 116-120

Gore J.A., Smith H.T., Smith B.S. and Gierhart W.A. (2008) Recent nesting of gull-billed terns on gravel roofs in Florida. Florida Field Naturalist 36 (4) 83-127

Hayashi E., Hayakawa M., Satou T. & Masuda N. (2002) Attraction of little terns to artificial roof-top breeding sites and their breeding success. Strix, 23, 143-148

Knaus, P., S. Antoniazza, S. Wechsler, J. Guélat, M. Kéry, N. Strebel & T. Sattler (2018): Swiss Breeding Bird Atlas 2013–2016. Distribution and population trends of birds in Switzerland and Liechtenstein. Swiss Ornithological Institute, Sempach.

Knowles, C. (2018) Forth Islands Tern Warden Season Report 2018. Unpublished Roseate Tern LIFE Project Report.

Knowles, C. (2019) Forth Islands Tern Warden Season Report 2019. Unpublished Roseate Tern LIFE Project Report.

Lampman K., Taylor M. & Blokpoel H. (1996) Caspian terns (Sterna caspia) breed successfully on a nesting raft. Colonial Waterbirds, 19, 135-138

Richards, M., & Morris, R. (1984). An Experimental Study of Nest Site Selection in Common Terns. Journal of Field Ornithology, 55(4), 457-466. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

Smith (2018a) Wave after wave of fledglings. Conservation success for the West Hayling Common Tern colony. RSPB Langstone and Chichester Blog. Accessed 22 January 2020.

Smith (2018b) Making a ‘tern table’: attempt 1. RSPB Langstone and Chichester Blog. Accessed 11.08.2020.

Smith R. (2015) Liverpool bay common terns. Dee Estuary Birding Monthly Newsletter June 2015 Accessed: 20/1/2020

Warraich T.N., Zambrano R., and Wright E.A. (2012) First Records of Least Terns Nesting on Non-Gravel Roofs. Southeastern Naturalist, 11(4):775-778.

Burgess N.D. & Hirons G.J.M. (1992) Creation and management of artificial nesting sites for wetland birds. Journal of Environmental Management, 34, 285-295

Cameron S. (2008) Roof-nesting by common terns and black skimmers in North Carolina. The Chat 72 (2) 44-45

Catry T., Ramos J.A., Catry I., Allen-Revez M. and Grade N. (2004) Are salinas a suitable alternative breeding habitat for Little Terns Sterna albifrons? Ibis 146, 247-257

Craik, C. (2013) The South Shian tern rafts. Eider December 2013 (No. 106)

Dunlop C.L., Blokpoel H. & Jarvie S. (1991) Nesting rafts as a management tool for a declining common tern (Sterna hirundo) colony. Colonial Waterbirds, 14, 116-120

Gore J.A., Smith H.T., Smith B.S. and Gierhart W.A. (2008) Recent nesting of gull-billed terns on gravel roofs in Florida. Florida Field Naturalist 36 (4) 83-127

Hayashi E., Hayakawa M., Satou T. & Masuda N. (2002) Attraction of little terns to artificial roof-top breeding sites and their breeding success. Strix, 23, 143-148

Knaus, P., S. Antoniazza, S. Wechsler, J. Guélat, M. Kéry, N. Strebel & T. Sattler (2018): Swiss Breeding Bird Atlas 2013–2016. Distribution and population trends of birds in Switzerland and Liechtenstein. Swiss Ornithological Institute, Sempach.

Knowles, C. (2018) Forth Islands Tern Warden Season Report 2018. Unpublished Roseate Tern LIFE Project Report.

Knowles, C. (2019) Forth Islands Tern Warden Season Report 2019. Unpublished Roseate Tern LIFE Project Report.

Lampman K., Taylor M. & Blokpoel H. (1996) Caspian terns (Sterna caspia) breed successfully on a nesting raft. Colonial Waterbirds, 19, 135-138

Richards, M., & Morris, R. (1984). An Experimental Study of Nest Site Selection in Common Terns. Journal of Field Ornithology, 55(4), 457-466. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

Smith (2018a) Wave after wave of fledglings. Conservation success for the West Hayling Common Tern colony. RSPB Langstone and Chichester Blog. Accessed 22 January 2020.

Smith (2018b) Making a ‘tern table’: attempt 1. RSPB Langstone and Chichester Blog. Accessed 11.08.2020.

Smith R. (2015) Liverpool bay common terns. Dee Estuary Birding Monthly Newsletter June 2015 Accessed: 20/1/2020

Warraich T.N., Zambrano R., and Wright E.A. (2012) First Records of Least Terns Nesting on Non-Gravel Roofs. Southeastern Naturalist, 11(4):775-778.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Clive Craik (South Shian), Peter Coffey (Merseyside Ringing Group), Craig Edwards (RSPB Dungeness), Paul Ellis (Fylde Bird Club) and Wez Smith (RSPB Langstone Harbour and West Hayling).

Thanks to Clive Craik (South Shian), Peter Coffey (Merseyside Ringing Group), Craig Edwards (RSPB Dungeness), Paul Ellis (Fylde Bird Club) and Wez Smith (RSPB Langstone Harbour and West Hayling).